The Phrase 'Third World' is Offensive and Vulgar

Exploring the ramifications of the phrase 'Third World' and why it should be deemed extremely offensive in modern vernacular

Give a thing a name and it will somehow come to be

George R. R. Martin, Dying of the Light

Language, as any honest student of history will tell you, is not merely the vehicle of thought—it is the very architecture of it. Words, far from being neutral, are instruments of power and prejudice, often as potent as any bullet. Some come pre-packaged with their barbarous provenance—slavery, lynchings, apartheid—and have earned their rightful place in the linguistic hall of infamy. Examples include the N-word in the US, the slur Paki in the UK, hēiguǐ in China, Arabush in Israel, Keling in Singapore/Malaysia, and Shina in Japan. Utter those words out aloud and you’ll rightly be met with public revulsion (or worse).

The examples above are ethnic slurs from a place in history where the world was a very different place, and with modernisation, we have rightly left these terms behind, where they belong. However, there are many other terms, subtly ensconced in the soft upholstery of academic respectability or geopolitical jargon, which do no less damage as they are arguably more expansive and cover a larger number of people or nations under one umbrella. Chief among these, and the subject of this article, is the sanctimoniously vague and insidiously patronising phrase: “Third World.”

Now, before you clutch your pearls or summon the X mob, let us be clear: I am not arguing that “Third World” and ethnic slurs are equivalent in sound or sentiment, only a fool or a provocateur would claim such a thing. But they do, rather disturbingly, perform similar ideological work. Both are shorthand for inferiority. Ethnic slurs reduce an entire race to subhuman status, stripping individuals of agency and dignity. “Third World,” dressed in the dusty tweeds of Cold War taxonomy, does something not altogether different: it consigns vast swathes of the globe, billions of people, to a category defined by lack, dysfunction, and neediness.

Originally coined to describe nations that refused to pick sides in the Soviet-American playground brawl of the mid-20th century, the term has since metastasised into a euphemism for poverty and chaos, code for the brown and black-skinned masses of the postcolonial world. That the phrase survived the Cold War and outlived the Second World (remember them?) should raise eyebrows, if not alarm bells. Today, “Third World” is wielded with the careless ease of someone discussing the weather. It turns diverse, dynamic societies into a single monolithic punchline; poverty porn for the global north, if you will.

Worse still, it’s a term that flatters the user with a sense of moral superiority. When a Western journalist or policymaker refers to “Third World problems,” they are not merely describing hardship; they are rehearsing a tired imperial script in which the West remains the measure of civilisation and the Rest a cautionary tale. It’s the linguistic equivalent of patting the developing world on the head while slipping their wallet from their back pocket.

And yet, unlike ethnic slurs and insults, “Third World” is still welcomed into polite conversation without so much as a raised eyebrow. It appears in editorials, university lectures, NGO brochures, and dinner party small talk—uttered without malice, but with no less consequence. This blithe acceptance is what makes it so pernicious. If ethnic slurs enshrine a racial caste system, then “Third World” enshrines a civilisational caste system—a global order where the West leads, and the rest trail behind, barefoot and grateful.

To compare the two, then, is not to equate their emotional resonance, but to expose a shared mechanism: the use of language to enforce hierarchies. If one term is rightly reviled for what it says about race, then the other should be interrogated for what it says about empire. Words do not merely describe the world—they shape it. And if we have learned anything from history, it is that the most dangerous prejudices are those hidden in plain speech.

Origins and historical context

To understand just how loaded and misleading the phrase “Third World” really is, it helps to go back to where it began. The term was first used in 1952 by French demographer Alfred Sauvy. Drawing inspiration from the “Third Estate” of pre-revolutionary France; the vast majority of common people who had no power but eventually overthrew the elite—Sauvy used the phrase to describe countries that were not aligned with either the NATO bloc or the Soviet Union during the Cold War. His intention was actually respectful: he saw these nations not as powerless, but as having their own agency, with the potential to challenge the global powers of the time.

Unfortunately, what started as a thoughtful metaphor quickly lost its dignity. By the 1960s and 70s, “Third World” had become a lazy, patronising label for countries in Asia, Africa, Latin America, and the Middle East—places that had only recently thrown off the chains of colonial rule and were now painted as unstable, poor, and perpetually in need of Western help. What was once a term of political non-alignment morphed into a euphemism for poverty, chaos, and incompetence. One can almost hear the clink of gin glasses in Western foreign ministries as the phrase made its way into policy memos and news reports: those people, the Third World lot.

And let’s be clear: this shift didn’t happen by accident. It wasn’t just a harmless change in language. It was a deliberate act of rebranding. The West, especially the former colonial powers now calling themselves “donor nations”, needed a neat way to talk about the mess left behind after centuries of exploitation. “Third World” became that convenient label in modern times. It allowed Western politicians and experts to discuss aid, debt, and development while subtly implying that these countries were struggling not because of what had been done to them, but because something was inherently wrong with them.

Meanwhile, ethnic slurs were performing a similar function on a different stage. It stripped individuals of complexity and humanity, reducing them to a sneer, a curse, a brand. These terms vs “Third World,” though vastly different in tone and historical texture, performed the same essential function: they marked out an “inferior other,” a class of people whose suffering could be discussed with the cool detachment of administrators and anthropologists, but never truly shared or understood.

That ethnic slurs are now widely recognised as unforgivable while “Third World” continues to enjoy polite society’s hospitality tells us less about the inherent offensiveness of each term than it does about our collective blind spots. The moral progress that made ethnic slurs radioactive has yet to fully reach our discussions of empire, development, and global order. We condemn racism at home, but seem remarkably tolerant of its linguistic cousins abroad.

To consign this phrase to the same dustbin as its more obviously noxious cousins is not to engage in some faddish linguistic purging. It is to acknowledge that words carry history, and history carries responsibility. If we are to discuss the nations of the so-called Global South, let us do so with language that reflects complexity, not condescension. That would be, at the very least, a beginning.

Language as a tool of power

Now, before the tutting begins from the defenders of “common usage” and the apologists for linguistic convenience, let us anticipate the counterargument: that “Third World” is simply a descriptive phrase, a matter of taxonomy, a term of art in the lexicon of development economists and geopoliticians who, bless them, only want to help. One might even hear that tired refrain: “Surely you’re not suggesting it’s as bad as other infamous ethnic slurs?”, as if offensiveness must be measured solely by how loudly it echoes across a dinner party table.

Let’s be unambiguous. The comparison is not between syllables, but between structures. Ethnic slurs are widely, and rightly, recognised as a verbal weapon of ethnic supremacy, forged in the foundries of colonialism and segregation, used to humiliate, brutalise, and define. But the phrase “Third World” is no less a relic of dominance. It performs a subtler, more insidious violence: it doesn’t scream its contempt, it murmurs it with a clipboard and a grant application.

Where ethnic slurs assert racial inferiority, “Third World” affirms civilisational inferiority. The implication is clear: these nations, these peoples, are perpetually lagging behind the West’s shining example. If only they could govern properly, build roads like the Germans, run elections like the Swedes, educate like the Finns, and file taxes like the Canadians, perhaps they too could one day join the shining pantheon of “developed nations.” Until then, they remain suspended in that purgatorial holding cell, too rich to be ignored, too poor to be respected, and always in need of guidance.

And here’s the real kicker: the phrase is not only degrading, it is also astonishingly lazy. It collapses the staggering diversity of dozens of countries, India and Haiti, Nigeria and Laos, Argentina and Afghanistan, into a single, amorphous blob of deficiency. No attention is paid to histories, cultures, innovations, or even economic performance. Botswana, a model of stability and growth, is flung into the same basket as failed states and war zones, all for the convenience of bureaucratic labelling.

The same linguistic flattening once enabled colonialism and segregation. Ethnic slurs didn’t see individuals; they saw castes. And while “Third World” may be dressed in more diplomatic attire, it too sees only what it wants to see: an undifferentiated mass of neediness, incompetence, and failure.

The worst part, of course, is that this term has been allowed to survive because it cloaks its contempt in the language of progress. It arrives with aid packages and development goals, discussed by well-meaning Westerners who’d blanch at being called racist, yet think nothing of describing entire continents with a phrase that implicitly ranks them beneath their own. One can only imagine the horror if someone referred to Appalachia or parts of Eastern Europe as Second-Class Citizens of the First World. Yet somehow, referring to Lagos, Dhaka, or Managua as part of the “Third” is considered acceptable.

This is the polite racism of global discourse, the structural snobbery of post-imperial paternalism. And it endures not because of malice, but because of inertia. The term has been grandfathered into our language, unquestioned, like a hideous family heirloom placed on the mantelpiece and dusted off every time a government agency releases a white paper.

Let us not be fooled by its academic credentials or its UN-sanctioned ambiguity. “Third World” is a relic, a Cold War artifact that no longer describes reality, but rather distorts it. It belongs, along with the other detritus of colonial doublethink, in the dustbin of intellectual dishonesty. And the sooner we hurl it there, the better.

Sociocultural impact

One of the more depressing spectacles of modern discourse is the serene, unthinking ease with which the phrase “Third World” is deployed, even by those who would claim to stand against inequality. Journalists who’d clutch their pearls at racial slurs happily refer to “Third World conditions” in America’s inner cities. Academics who pen tear-stained articles about intersectionality still drop the phrase in conference papers, unaware, or unwilling to admit, that their terminology is soaked in the same imperial marinade they claim to critique. And let us not forget the globetrotting charity worker, who, after a week in Nairobi or Dhaka, returns home laden with photos, stories, and a renewed sense of Western superiority masked as benevolence. “You simply wouldn’t believe the poverty,” they say, no doubt while clutching a flat white in Islington.

This casual use is not incidental. It’s precisely the casualness that does the damage. Ethnic slurs, rightly, cause audible discomfort when uttered, even in quotation or critique, because society has absorbed the weight of its history. To speak it aloud is to touch a live wire. But “Third World”? That term floats unchallenged across the dinner tables of the bien-pensant classes. It gets printed, broadcast, and taught. It shows up in policy documents and primary school textbooks. It is worn, not like a slur, but like a lanyard, signalling the speaker’s worldly concern, without the burden of thought.

Yet behind the apparent neutrality of the term lies a worldview as condescending as any colonial governor’s travelogue. It tells us that the world is still divided into those who know and those who must be taught; into those who develop and those who are to be developed. It constructs a hierarchy with the West eternally perched at the top, doling out progress like sugar cubes to the grateful natives. This is not an analysis. It is theology masquerading as geopolitics. And, like all bad theology, it demands faith in things demonstrably untrue: that wealth is a proxy for virtue, that Western modernity is the universal goal, and that the scars of colonialism are merely the birthmarks of progress.

Indeed, the psychological toll of such language should not be underestimated. Entire generations of children in the so-called “Third World” grow up internalising the idea that their countries are somehow broken by default. The phrase carries with it the low hum of inferiority, inaudible at first, but pervasive, like background radiation. It informs how people are treated at airports, in boardrooms, at visa offices, and on the international stage. It seeps into the soul, whispering: You come from a place of failure.

This is not just a linguistic critique; it is a moral one. To persist in using such language is to participate, however unconsciously, in a system that normalises inequality and mythologises the global order. It excuses the grotesque imbalance in wealth, power, and opportunity as natural, as historical inevitability, rather than as the legacy of theft and domination.

Let us be plain: just as ethnic slurs codify racial hierarchy into a single syllable, “Third World” encodes geopolitical supremacy into two. It is not a descriptor; it is a verdict. And the fact that the accused have never been given a proper trial makes the usage all the more insidious.

To abolish this phrase from respectable conversation is not to surrender to political correctness. It is to reclaim intellectual honesty. It is to insist that if we must speak of the world, we do so in terms that reflect its complexity, its plurality, and its shared humanity, not in terms that flatter our own position atop a rigged pyramid.

Counterarguments and nuance

To suggest, without flinching, that the phrase “Third World” is as offensive as ethnic slurs is to enter a conversational minefield wearing clogs. The latter, after all, are universally recognised as a term of pure racial malice. In contrast, “Third World” appears in peer-reviewed journals, United Nations documents, and the mouthings of otherwise decent dinner party guests. To compare the two, some will protest, is to engage in moral hyperbole. But this argument is not an exercise in false equivalence; it is a plea for intellectual consistency. If we are serious about dismantling the architecture of oppression, then we must examine not just the bricks, but the mortar: the language that holds the whole edifice together.

One of the more persistent evasions is that “Third World” is merely obsolete, not offensive, as though being archaic is somehow absolving. We’re told it lacks the venom, the intent, the barbed wire emotional payload of ethnic slurs. But anyone with even a passing acquaintance with history should know that intent is not the sole measure of impact. A man may drive a tank over your garden while whistling innocently; the flowers are flattened all the same. “Third World” is not shouted in the streets by torch-wielding bigots, but it whispers, with bureaucratic calm, that some countries are permanently relegated to the children’s table of civilisation. It is, in short, the linguistic wing of the IMF.

This semantic sleight of hand, whereby entire nations are bracketed into inferiority by the stroke of a pen, amounts to what Orwell might have called “politics in the guise of classification.” The Global North (a smug term in its own right) has long reserved the right to name the rest of the world, much as a colonial officer might name a new railway station after his aunt. The phrase “Third World” is less an objective descriptor than a low-grade insult in a mortarboard, cloaked in the respectability of development discourse.

Now, one might object: “But ethnic slurs target a race; ‘Third World’ refers to whole regions!” Indeed. And this makes the matter worse, not better. Ethnic slurs, vicious though it is, single out individuals. “Third World” casts a net over billions, over entire peoples, cultures, and histories, and declares, with all the elegance of a telegram from the Raj, that they are wanting. It flattens centuries of nuance, diversity, and achievement into a single shrug of global condescension.

Let us anticipate the next defence: “But aren’t all these alternatives, ‘developing world’, ‘Global South’, etc., just euphemistic reshufflings?” Quite right. Many are. The term “developing” implies that progress is a linear pilgrimage toward Western suburbia, complete with Netflix and municipal recycling. “Global South” may have the virtue of geographic politeness, but it’s used interchangeably with the same sneering undertones. Replacing the label is only part of the task. What’s needed is not a change of vocabulary so much as a change of mind: a refusal to see the world as a schoolyard, with the West as headmaster and the rest as remedial pupils.

In the end, this argument does not hinge on whether “Third World” and ethnic slurs are historical twins. They are not. Their genealogies are distinct, their emotional timbre different. What they share, however, is a function: both compress human beings into caricature, both elevate the speaker while diminishing the subject, and both are designed, consciously or not, to make inequality feel natural. They are the linguistic equivalents of a velvet rope, separating the world into VIPs and everyone else.

To acknowledge this is not to dilute the gravity of racial slurs; it is to extend our critical faculties across the full terrain of oppression. We must abandon the comfortable illusion that some words only offend when shouted. Sometimes, the most pernicious terms are the ones that pass quietly, politely, unchallenged, like a diplomat carrying stolen goods under diplomatic immunity.

Words matter. Not because they are symbols of feelings, but because they are tools of power. And if we are to take our principles seriously, if we are to speak of justice without gagging on hypocrisy, then we must consign “Third World” to the same dustbin where the world’s other euphemisms for domination have gone to rot..

Alternative language

If the phrase “Third World” is, as we've established, offensive, reductive, and hopelessly archaic, akin to describing surgery with leeches, then what, one might reasonably ask, ought we to say instead? How do we speak of global inequality, regional disparity, or developmental gaps without lapsing into the patronising lexicon of empire and economic snobbery? This is not a matter of mere lexical hygiene or the linguistic whims of the easily offended. No, it is a question of intellectual precision and moral seriousness. Language, as Orwell reminded us, not only reflects reality, but it also constructs it.

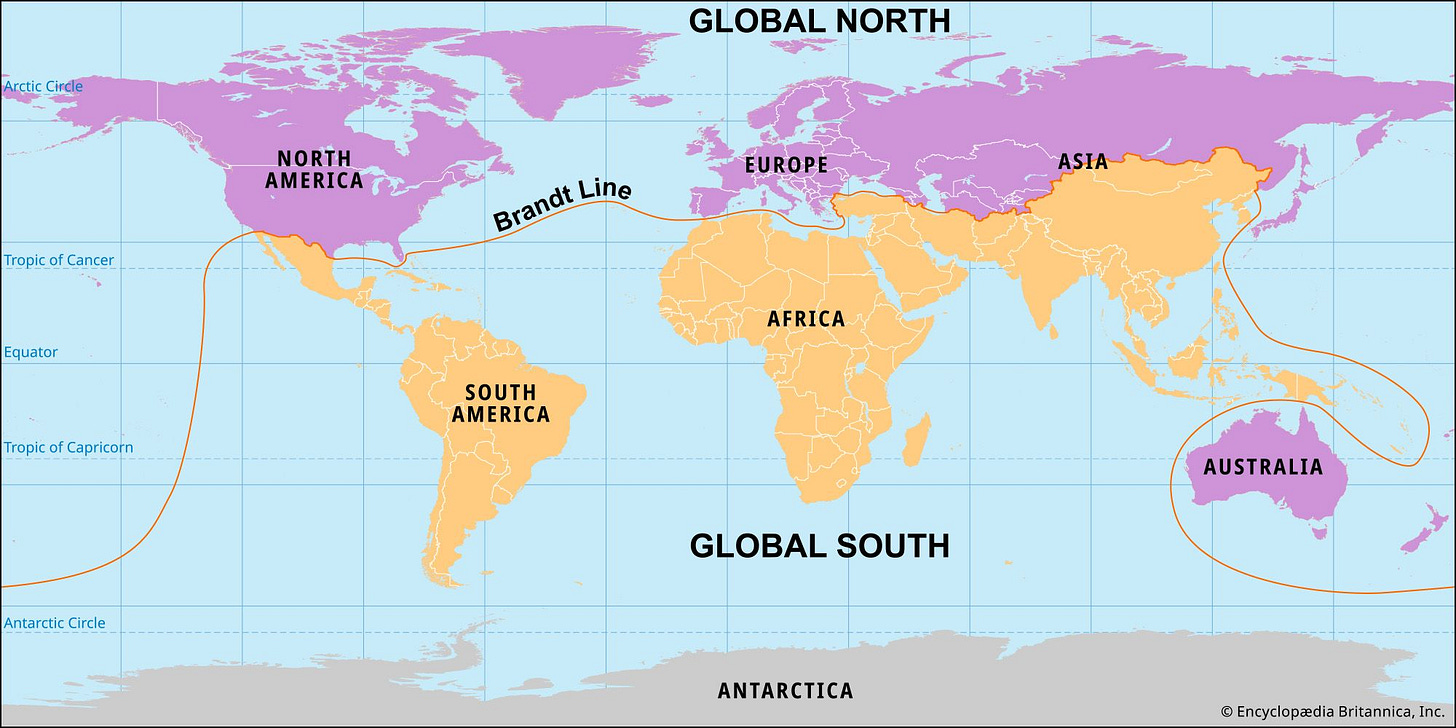

Among the more popular replacements is “Global South”, a term which, at the very least, has the good manners not to imply intrinsic backwardness. It gestures, albeit somewhat awkwardly, toward a shared history of colonial exploitation, debt traps, resource plunder, and geopolitical chess-playing by the usual suspects. While the phrase occasionally requires a globe and a stiff drink to make sense of—Mexico, India, and China being geographically north of several “Global North” nations—it at least avoids the odious suggestion that billions of people are stuck in some civilisational waiting room, forever queuing for progress.

Then we have the economist’s favourite mouthful: “low- and middle-income countries” (LMICs). This sounds as though a malfunctioning spreadsheet produced it. True, it offers a superficially neutral, numerical approach, but numbers can be as ideological as any scripture. When we define nations solely by GDP brackets, we reduce vast, diverse societies into digits on a World Bank PowerPoint. We overlook history, governance, culture, resilience, and resistance. Worse, we accept without question that a nation’s worth is defined by its income, as if moral legitimacy were issued alongside a credit rating.

“Developing countries” is still wheeled out with regularity, often by people who haven't thought very hard about what development means or who gets to define it. This phrase assumes that all countries are trudging dutifully toward some universal finish line, one presumably located in Western Europe, furnished with IKEA furniture and broadband. It presupposes that industrial capitalism, consumer democracy, and secular liberalism are the telos of all civilisation. Heaven help any country with the temerity to think otherwise.

A more honest approach, though admittedly less punchy on a headline, is to describe countries in terms that reflect their actual circumstances: postcolonial states, resource-rich economies suffering institutional fragility, nations grappling with structural inequality, and so forth. These phrases are admittedly a mouthful, yes, but clarity often demands effort. And there is something to be said for trading glibness for accuracy. A complex reality deserves more than a lazy label.

In other cases, regional identifiers may suffice. Sub-Saharan Africa, Southeast Asia, and Latin America, provided we don't wield these as euphemisms for poverty or dysfunction, are useful and precise. Better still, we might name countries directly and discuss their particular contexts. Imagine that: speaking of people and places as though they were distinct and worthy of individual consideration. Radical, I know.

But let us not be naïve. There is no magic phrase that will capture the world’s inequalities in a single turn of phrase. Nor should we want one. The aim is not to sanitise language until it’s politically inert, nor to smother all geopolitical discourse in euphemism. The goal is to confront reality, its causes, its histories, its injustices, with the clarity and respect it demands. To challenge lazy speech is to challenge lazy thought.

The endurance of “Third World” as a descriptor owes more to intellectual sloth than semantic necessity. It's a linguistic relic from the Cold War era, still propped up in development discourse because it’s easier than thinking. But ease, as ever, is the enemy of truth.

Just as the rejection of ethnic slurs in polite society was not merely about syllables but about the social and historical reckoning they symbolise, so too the discarding of “Third World” is not pedantry, it is protest. Language cannot dismantle injustice on its own, but it can mark the beginning of such a dismantling. Words are where empires begin, and sometimes, where they end.

Conclusion

Language, we should remind ourselves, is not a neutral conduit for ideas but often the sly accomplice of power. It does not merely describe the world, it decides what sort of world we inhabit and who gets to sit at the grown-ups’ table. Take, for instance, the phrase “Third World”. Like the infamous N-word, yes, that word, its provenance, payload, and pitch may differ, but both perform a depressingly similar civic function: they reduce, they flatten, they rank. They are the linguistic equivalents of summary judgement, pronounced without trial and carrying the weight of inherited contempt.

One hails from the colonial drawing room, the other from the slave plantation. One was cloaked in the argot of geopolitics, the other in the lexicon of racial tyranny. But both were birthed in systems of unambiguous dominance, and both survive, not by accident, but because they are so damnably useful to those systems. This is the argument at hand: not that the N-word and “Third World” are twins separated at birth, but that they share a family resemblance in the way they mark people and places as inherently inferior.

Predictably, this parallel causes distress. And fair enough, the N-word carries with it the full horror of racial subjugation, lynching ropes, and Jim Crow laws. “Third World”, by comparison, sounds like something mumbled by a conference panellist in Geneva. It masquerades as objective, even polite. But this politeness is a cover story. It whispers assumptions about civilisational inadequacy, economic impotence, and political ineptitude. It rolls off the tongue in newsrooms and dinner parties precisely because its violence is not shouted from pulpits but etched silently into maps and budgets. Subtle, yes. Harmless? Not in the least.

This article has attempted to lay bare the pedigree of the term, its Cold War origins, its gradual evolution into a shorthand for suffering, and its role as a quiet enforcer of global hierarchies. It has drawn parallels with ethnic slurs, not to collapse histories into a crude equivalence, but to illuminate the comparable ways in which language ossifies injustice and embalms bigotry in everyday speech. We’ve surveyed the usual objections, intent, context, alternatives, and countered not with moralising, but with precision. We’ve even proposed a few replacements, albeit with the caveat that no term can do justice to a planet’s worth of complexity.

Language, after all, is the scaffolding of civilisation. It reflects our values, yes, but it also constructs them. To persist in calling entire swathes of humanity “Third World” is not a reflection of their condition, but of our own intellectual laziness and moral complacency. This is not a sterile quarrel over diction; it is a matter of justice.

We now inhabit a century where our fates are increasingly entangled. Viruses, carbon emissions, and financial collapses do not pause at passport control. In such a context, the binary of “First” and “Third” is not only obsolete, it is dangerously misleading. It encourages a condescending charity where cooperation is needed, a smug superiority when solidarity is essential.

If we’re to build a saner, fairer world, then let us begin where all revolutions worth their salt do, with our words. Let us consign “Third World” to the same linguistic oubliette as other relics of unthinking prejudice. As with ethnic slurs, its continued use reveals far more about those who wield it than those at whom it is directed. It is time to stop cloaking condescension in cartographic euphemism. The phrase doesn’t describe; it demeans. And in an age that demands moral clarity, that is reason enough to retire it.

☕ Love this content? Fuel our writing!

Buy us a coffee and join our caffeinated circle of supporters. Every bean counts!

By our standards (by the goals and values which we prioritize), the "developing" world IS "civilizationally inferior". Human capital, international development, foreign aid - none of these concepts would be necessary if it wasn't.

Yes, language can be a tool of oppression and prejudice (although more often perhaps it's just a reflection of it). But trying to erase any distinction or hierarchy or value judgement in language is an equally political goal, and it can be equally false. Westerners often like to pretend that there's a kind of innate worthiness to ALL cultures. Of course, this conceit falls apart as soon as they begin talking about ACTUAL foreign cultures, or history... or when they must choose a place to live.

By the standards of the modern world, the developed world is a safer, richer, easier, more opportunity-laden setting in which to build a life. It is better, and the developing world is worse. I'm not defending the term "third world" but it shouldn't be abandoned simply because it generalizes or stigmatizes or makes value judgements. Value judgements are necessary and unavoidable. Some things (cultures, beliefs, people) are simply better than others.

https://jmpolemic.substack.com/p/white-supremacy

So you espouse speech fascism and silencing the Truth, no matter how painful- triggering delusion & zero improvement where non-performers never improve without the needed criticism and peer pressure. This actually is evil- keeps mediocre countries mediocre. Be proud of your culture even though it sux. Be proud even when most of your country yearns to emigrate. Encourage host countries to virtue-signal accommodate immigrants by adopting the customs of inferior cultures, instead of mandating them to assimilate & adopt the better habits that contributed to making the host nation a world leader and immigration magnet.

Bravo. Make all cultures equally mediocre / discourage individual progress.