The Integration Paradox: Why We're Solving the Wrong Problem

From Singapore's Social Engineering to Britain's Cultural Hierarchies - Why Integration Defies Simple Solutions

Picture this: you're eight years old, walking into a classroom where everyone looks different from you. Not just different in the way all eight-year-olds are uniquely weird, but different in that way that makes adults whisper at school gates. You're the only brown kid in a sea of white faces in suburban Britain. Your parents, meanwhile, navigate their professional lives with competence but return home to a social circle that looks nothing like the neighbourhood around them.

The playground becomes your first laboratory in social dynamics. You learn to code-switch before you even know the term - adopting different versions of yourself for different audiences. At school, you perfect your English accent, laugh at jokes about cricket, and pretend not to notice when classmates assume you're good at maths or ask where you're "really" from. At home, you slip back into familiar rhythms - the smell of spices your friends can't pronounce, conversations that weave between languages, cultural references that would be met with blank stares elsewhere. You become fluent in translation, not just of words but of entire ways of being. Birthday parties become exercises in cultural navigation: do you explain why you can't eat certain foods, or do you quietly pick around them? Do you invite school friends to your house, knowing they'll encounter unfamiliar customs, or do you keep those worlds carefully separate? These aren't grand moments of discrimination - they're the thousand tiny calculations that shape how you move through the world, each one teaching you that integration isn't a destination but a constant performance.

This was my introduction to what academics grandly call "immigrant integration." Spoiler alert: it's complicated.

The Problem That Might Not Be a Problem

Here's the uncomfortable question we need to ask: when politicians and pundits wring their hands about immigrant integration, what exactly are they worried about? Is there genuinely a crisis of social cohesion threatening to tear apart the fabric of society? Or have we been sold a narrative by people who benefit from keeping us anxious about our neighbours?

Recent research shows that racial justice issues have actually become less salient to voters since 2020, with Biden emerging as a less racially polarising figure than Trump. Yet immigration continues to dominate headlines, often framed through an explicitly radicalised lens. The rhetoric of "invasion" and crisis keeps any real solutions at a distance, while the actual data tells a more nuanced story.

Consider this: immigrant integration touches upon virtually all institutions that promote development and growth within society. When it works, it builds communities that are stronger economically and more inclusive socially. The question isn't whether integration matters, but rather who gets to define what successful integration looks like.

Singapore's Social Engineering Experiment

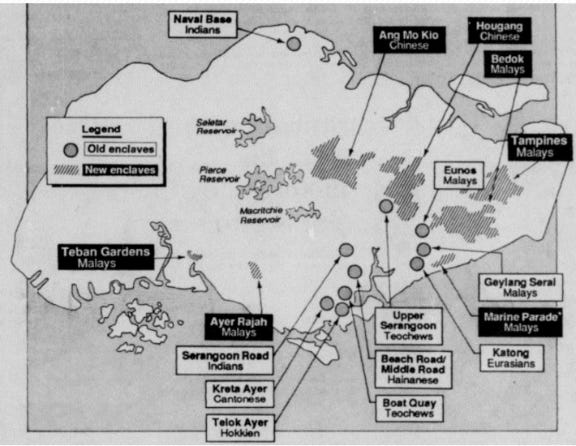

Few countries have taken as direct an approach to integration as Singapore. Since 1989, the city-state has enforced its Ethnic Integration Policy (EIP), which places quotas on how many residents of one racial group can live in a building, ensuring each apartment complex reflects Singapore's true ethnic makeup.

It's social engineering at its most literal. Tharman Shanmugaratnam called it "the most intrusive social policy in Singapore", yet also perhaps the most important. The logic is seductive in its simplicity: if children of different ethnicities grow up together, attend the same schools, and play in the same void decks, surely they'll develop the elusive "kampong spirit" of community harmony.

But here's where it gets interesting. HDBs have still seen their fair share of racially charged incidents that reveal a trembling link between growing up together and integration. Physical proximity doesn't automatically translate to social connection. You can mandate where people live, but you can't legislate friendship.

The Singapore model assumes the government knows best, trading personal liberty for what it sees as societal harmony. It's a fascinating counterpoint to the Western liberal approach, which generally privileges individual choice. Yet neither model has cracked the code completely.

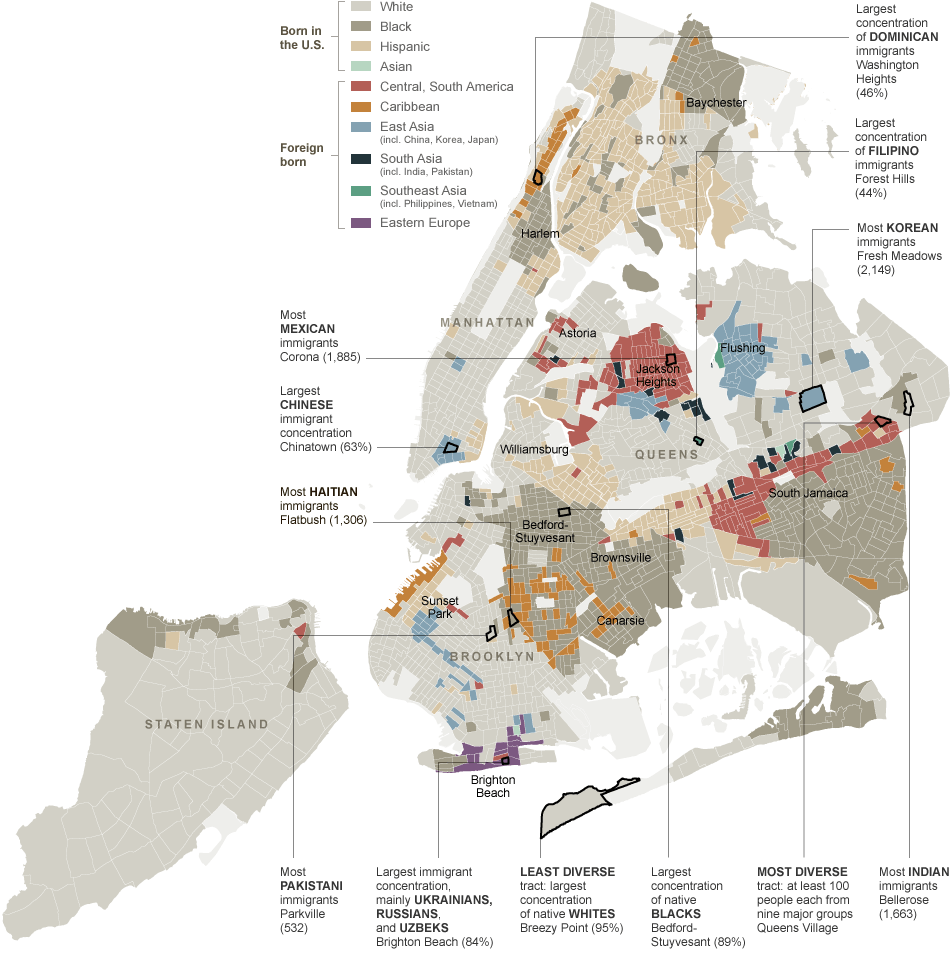

The contrasts become stark when you examine New York's laissez-faire approach alongside Singapore's orchestrated integration. Where Singapore mandates ethnic quotas in every housing block, New York has evolved into one of America's most segregated cities through market forces and historical patterns - with neighbourhoods like Chinatown, Little Italy, and Jackson Heights in Queens forming organic ethnic enclaves. Manhattan's Upper East Side remains 80% white while the Bronx is 44% Hispanic, creating a patchwork of communities that often exist in parallel rather than intersection. Yet this seemingly chaotic arrangement has produced its own form of vibrancy: New York's cultural dynamism emerges from the tension between distinct communities rather than mandated mixing. The city's strength lies not in engineered harmony but in productive friction - the constant negotiation between different groups sharing limited space. It's messy, sometimes contentious, but undeniably creative. Singapore achieves surface-level integration through policy; New York stumbles toward something messier but perhaps more authentic through the unpredictable alchemy of eight million people choosing how to live together.

The British Contradiction

My own experience in the UK reveals a different kind of paradox. Britain prides itself on multiculturalism and tolerance, yet research shows that migrants and the UK-born report broadly similar levels of neighbourhood social cohesion, while actual social circles often remain stubbornly separate.

Growing up, I saw this firsthand. My parents were successful professionals who contributed to the economy, paid taxes, spoke fluent English, and participated in civic life. By any reasonable metric, they were "integrated." Yet, their social world mostly stayed separate from their white British colleagues and neighbors. Was this a failure of integration, or just the natural way communities form based on shared experience and culture?

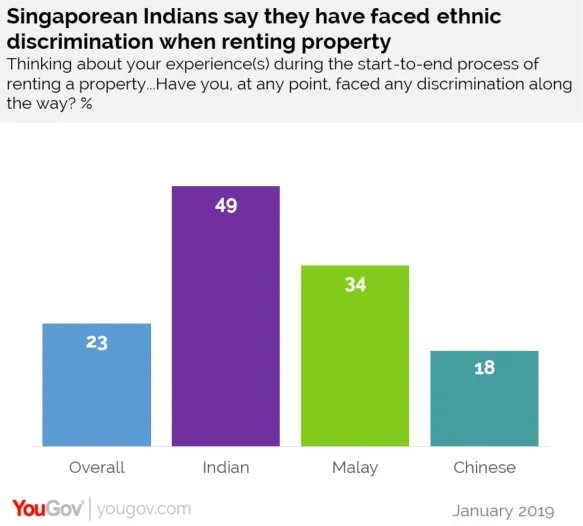

British people clearly distinguish between migrants based on their country of origin, favouring those who are white, English-speaking, and from European countries, while they are least receptive to non-white migrants from non-European or Muslim countries. This "ethnic hierarchy" indicates that challenges with integration may be more related to host society attitudes than to immigrant behaviour.

But this racial lens tells only part of the story. The concept of "cultural proximity" offers a more nuanced framework - one that explains why Polish plumbers might face initial resistance but eventual acceptance, while Romanian Roma communities encounter persistent hostility despite shared European heritage. More tellingly, Irish Travellers - who are ethnically white and culturally Celtic - remain among Britain's most marginalised groups, facing discrimination that cuts across political lines. Even well-integrated Polish communities in places like Boston, Lincolnshire, have experienced tensions that transcend simple racial categories. The otherness isn't just about skin color; it's about perceived compatibility with British social norms, economic competition, and cultural practices. A white American banker slots seamlessly into London society while a white Bulgarian construction worker might not, suggesting that integration operates on multiple axes simultaneously. This complicates the neat narrative of racial hierarchy - though it doesn't eliminate it. Rather, it reveals integration as a complex negotiation between race, class, culture, and economics, where even successful adaptation can be undermined by deep-seated anxieties about cultural change.

Denmark's Shifting Goalposts

Denmark provides perhaps the clearest example of how integration goals can change with political influences. Despite the employment rate of non-Western immigrant men rising from 53% in 2015 to 69% in 2022, and their educational achievements improving significantly, the country has also tightened its immigration policies to the point that all humanitarian residence permits are now issued for temporary stays.

The paradox is striking: immigrants are succeeding according to traditional metrics like employment, education, and language skills, yet they face policies aimed at preventing their stay. It's like running a race where the finish line keeps moving farther away.

This reveals integration's dirty secret: it's often less about immigrant performance than host society anxiety. Denmark's immigrants are doing exactly what they were asked to do - learning Danish, finding jobs, contributing to society - yet the goalposts have shifted from "integrate and belong" to "integrate but don't expect to stay." The message becomes impossible to decode: succeed enough to be useful, but not so much that you feel entitled to permanence. It exposes integration as a moving target, shaped more by political winds than empirical outcomes. When success is met with increased restrictions, the exercise stops being about genuine inclusion and becomes something else entirely - a form of managed exclusion dressed up in the language of standards and merit. The immigrants caught in this system face an impossible bind: their very success becomes evidence that the system works, justifying policies that ensure they can never fully belong to the society they've successfully joined.

The Real Problem: Who's Telling the Story?

Perhaps the most damaging aspect of the integration debate is how it has been weaponised. Immigration policy has aligned with shifts from European to Latin American, Asian, and African newcomers, often within racially charged debates. The "problem" of integration appears to have emerged precisely when immigrants ceased to be predominantly white.

Trump's anti-immigrant rhetoric included claims that immigrants are "poisoning the blood of our country" and calling them "animals". This isn't about integration policy; it's about dehumanisation. When integration is discussed through this lens, no amount of language learning, employment success, or civic participation will ever be enough.

The Freedom vs. Harmony Dance

The tension between personal freedom and societal harmony plays out differently around the world. Singapore sacrifices individual choice for engineered diversity. Denmark demands conformity while planning for change over time. The UK advocates for multiculturalism while keeping social boundaries intact. The US swings between embracing diversity and fearing it.

Each approach reveals something about national anxieties and aspirations. But they all share a common flaw: they treat integration as something done to immigrants rather than a two-way process involving the entire society.

Beyond the False Binary

Research indicates that immigrants' ongoing identification with their home country does not prevent them from forming an identity linked to their destination country. Both can coexist. This challenges the basic idea that integration requires choosing a side.

My own life reflects this duality. Most of my friends today come from around the world, not because I haven't integrated, but because modern city life fosters these cosmopolitan social circles. Is this a problem to be fixed or just the reality of 21st-century diversity?

Research on second-generation outcomes is promising: children of immigrants reach significant economic parity with children of natives in many countries, though current methods tend to work better for daughters than sons. Over time, it appears, much of the integration progress happens naturally, beyond what policy alone can achieve.

The Integration We're Not Talking About

Here's what rarely gets discussed: maybe the natives also need integrating. In our globalized world, the ability to navigate diversity, communicate across cultures, and collaborate with people from different backgrounds isn't just nice to have; it's essential. The white British kids in my childhood classroom who never learned to connect across differences might be the ones who are poorly integrated into today's reality.

Research using British data shows that people with "bridging ties" connecting individuals from different groups have less negative experiences with diversity. The problem isn't diversity itself but the lack of tools and opportunities to build these bridges.

Reframing the Conversation

What if we stopped asking "How do we integrate immigrants?" and started asking "How do we build societies where difference is a strength rather than a threat?"

This isn't just semantic gymnastics. Integration tends to improve with duration of residence in most countries, according to available data. Given time and opportunity, people generally figure out how to live together. The crisis narrative serves those who benefit from division, not those seeking solutions.

The evidence suggests that successful integration requires:

Economic opportunities that don't discriminate

Educational systems that value diverse backgrounds

Housing policies that prevent extreme segregation without forcing proximity

Legal frameworks that provide security and paths to permanence

Social attitudes that see diversity as normal rather than threatening

The Uncomfortable Truth

Perhaps the most uncomfortable truth is that the "integration problem" might be more about our discomfort with change than any real crisis. Societies have always welcomed newcomers, adapted, and evolved. The difference now is that we're doing it under the scrutiny of 24-hour news cycles and social media outrage machines.

My parents never had white British friends, but they contributed to their community, raised children who navigated both worlds, and built lives of meaning and purpose. If that's not true integration, maybe we need better definitions. Or perhaps we should stop obsessing over integration entirely and focus on creating societies where everyone, regardless of background, has the chance to thrive.

The conflict between personal liberty and societal harmony isn't just an intriguing issue we are addressing in real time; it reflects the human condition. Immigration simply highlights this. And visibility, no matter how uncomfortable, is the first step toward honest conversations.

Ultimately, the question isn't whether we can successfully integrate immigrants. History demonstrates that we can and do, again and again, despite our best efforts to hinder it. The real question is whether we will let fear and prejudice control the process, or whether we'll have the courage to envision and create something better.

After all, in a world where an eight-year-old immigrant can grow up questioning the very foundations of integration policy, anything becomes possible. Even progress.

☕ Love this content? Fuel our writing!

Buy us a coffee and join our caffeinated circle of supporters. Every bean counts!

thanks for your reply. i have worked for many years in India, Nigeria and other developing countries. If I had a white child in their country and send it to school there and then to claim it was an Indian or Nigerian child they would just laugh at me.

English people are people descended from the people who have lived in England for hundreds of years in the same way Inuit people are those descended from Inuits and not people who have moved in a few decades ago. Your kids may be legally British citizens but they are not of English ethnicity and will never be.

English people were a majority in England for centuries: now they are less than 90% and minorities in London and Birmingham. The trends are clear: if we continue as we have been doing then English people will be a minority this century.

Do you think if English people had replaced Indians in India the way they did Aborigines in Australia that India would still be India? Do you think the replaced Indians would be happy with being replaced by English even if the new "Indians" all spoke Hindu? That is not human nature. A small number of immigrants can easily be integrated and fit in. Once they get to 20% or 60% or 80% this is not what happens.

Are there not issues of quantity as well as ability and willingness to integrate and be integrated? What about the schools where white English children are minority, the school classes where they are absent? Hundreds of millions of people would like to migrate to England and Denmark. Is the only consideration ability to pay tax? Then English are on-track to be a minority in their own country. India, Pakistan, Nigeria would not accept this. Why is it ok for them to have their own country but not England? Just asking.