The Innovation Trap: Why Humanity Can't Afford to Play It Safe

From feudal stagnation to frontier paralysis: why progress requires the freedom to fail

There were humans long before there was history. Animals much like modern humans first appeared about 2.5 million years ago. But for countless generations they did not stand out from the myriad other organisms that populated the planet.

- Yuval Noah Harari (Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind)

For roughly ten thousand years after humans worked out how to grow crops, virtually nothing happened. A peasant in 15th century England would have found life in ancient Sumeria disappointingly familiar. Different gods, marginally better ploughs, but essentially the same brutal equation: work yourself to exhaustion, produce barely enough to survive, die young, repeat.

This wasn’t because our ancestors were dim. Humans had already domesticated animals, invented writing, built the pyramids, and developed mathematics sophisticated enough to predict eclipses. The problem wasn’t cognitive capacity. The problem was that being clever was utterly pointless.

Under feudalism, innovation was the world’s worst investment. Devise a brilliant new farming technique? Congratulations, your lord now extracts more grain whilst you remain exactly as miserable as before. Invent a superior tool? Lovely. You still don’t own the land, the crops, or your own time. Suggest doing things differently? Excellent way to make enemies, disrupt the social order, and possibly get yourself killed, all for precisely zero upside.

The rational choice was obvious: do exactly what everyone else does, exactly as they’ve always done it. And so, for millennia, that’s what humans did. We weren’t stuck because we lacked genius. We were stuck because genius had nowhere to go.

This should terrify us. Because we’re running out of time to not be stuck.

What is innovation?

Before we go further, we need to be precise about what innovation actually means, because the word has been tortured into meaninglessness by corporate marketing departments and government propaganda.

Real innovation (the kind that matters, the kind that changes human civilisation) isn’t about making things incrementally better or throwing enormous resources at established technologies until they scale. Building the world’s largest electric vehicle industry by subsidising the hell out of it isn’t innovation. It’s industrial policy. Developing sophisticated AI by scraping every piece of data you can access and running it through known architectures on massive server farms isn’t innovation. It’s brute force engineering.

Both are impressive. Both require technical competence. Neither is what we’re talking about.

True innovation is paradigm-breaking. It’s the shift from whale oil to petroleum in the 1850s, which destroyed an entire industry overnight and reconfigured global energy. It’s the jump from horses to automobiles, from telegrams to telephones, from filing cabinets to databases. It’s OpenAI’s GPT models making traditional search engines suddenly look quaint, or mRNA vaccines rewriting pharmaceutical development. These aren’t improvements on what existed. They’re fundamentally different ways of solving problems, often problems people didn’t realise they had.

The distinction matters because paradigm-shifting innovation requires something psychologically different from scaling existing technologies. Scaling requires discipline, resources, and execution (things hierarchical, organised societies excel at). Paradigm shifts require someone to look at the established way of doing things and think, “What if we’re asking the wrong question entirely?” They require tolerance for ideas that sound absurd, for approaches that violate conventional wisdom, for spectacular failures that teach you what doesn’t work.

You can command an industry to build better batteries. You cannot command someone to invent a replacement for batteries that makes the entire concept obsolete. The first happens through directed effort and resources. The second happens through exploration, experimentation, and the freedom to pursue ideas that will probably fail.

Many economies claim to be innovative whilst primarily excelling at scaling, refinement, and impressive execution. These capabilities are genuinely valuable. But being the world’s best at building electric vehicles using lithium-ion battery technology someone else invented isn’t the same as creating the next energy paradigm that makes lithium-ion batteries irrelevant.

The question facing humanity isn’t whether we can build more of what we already know how to build. It’s whether we can discover what we don’t yet know we need. And that requires a fundamentally different approach to risk, failure, and experimentation.

The Stakes Have Changed

Climate change is accelerating faster than predicted. Global population is set to peak and then plummet in ways that will shatter pension systems and economic models. Antibiotic resistance is quietly preparing to drag us back to a pre-penicillin world where minor infections kill. Inequality is reaching levels that historically precede either revolution or collapse. AI might save us or doom us, possibly both, and we have perhaps a decade to work out which.

These aren’t abstract future problems for someone else to solve. They’re happening now, and the window for solutions is closing. We need breakthrough innovations in energy, materials science, biotechnology, social organisation, and probably half a dozen fields we haven’t even properly named yet. We need them fast, and we need them to actually work.

It’s easy to take this for granted in the West, where the transformative power of innovation has become invisible precisely because it worked so well. But the impact is staggering when you look at it plainly. Smallpox killed roughly 300 million people in the 20th century alone before vaccination eradicated it entirely in 1980. Polio paralysed hundreds of thousands of children annually across Africa and South Asia until vaccine campaigns reduced cases by 99%. These weren’t incremental improvements. They were paradigm shifts that eliminated ancient terrors.

The Green Revolution in the 1960s prevented the mass starvation that experts confidently predicted would kill hundreds of millions across Asia. Norman Borlaug’s wheat varieties, combined with new farming techniques, allowed India and Pakistan to become food self-sufficient. One estimate suggests the innovations saved a billion lives. A billion. Not through perfect planning but through someone trying something that conventional wisdom said wouldn’t work.

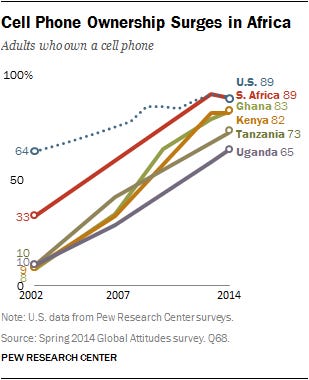

The mobile phone revolution in Africa leapfrogged the need for landline infrastructure entirely, bringing connectivity and mobile banking to hundreds of millions who would have waited decades for copper wires. M-Pesa in Kenya transformed an economy by letting people transfer money via text message, something that seemed absurd until it worked. Container shipping, invented in the 1950s, cut the cost of global trade by 90% and lifted billions out of poverty by making international commerce feasible for developing economies.

These innovations didn’t just make life marginally better. They fundamentally altered what was possible, often for the people who needed it most desperately.

Which means we desperately need people trying lots of things, most of which will fail spectacularly.

This is not the moment in human history to optimise for safety.

The First Unlock: Making Success Worth It

The breakthrough from feudal stagnation came gradually, then suddenly. Property rights emerged. Enforceable contracts became possible. Patent systems appeared. Markets started to function. And for the first time in human history, a person with a clever idea could actually benefit from it.

This was revolutionary. Not the ideas themselves, humans had always had ideas, but the incentive structure. Suddenly, the merchant who found a better trade route got rich rather than simply making their lord richer. The inventor who created a useful device could sell it. The entrepreneur who took risks could capture rewards.

As Acemoglu and Robinson argue in “Why Nations Fail,” “Inclusive economic institutions that enforce property rights, create a level playing field, and encourage investments in new technologies and skills are more conducive to economic growth than extractive economic institutions that are structured to extract resources from the many by the few.” The shift from extractive to inclusive institutions was nothing less than the unlocking of human potential on a civilisational scale.

Beyond Traditional Explanations: A Nobel Prize-Winning Theory of National Prosperity

This book will show that while economic institutions are critical for determining whether a country is poor or prosperous, it is politics and political institutions that determine what economic institutions a country has. Daron Acemoğlu, Why Nations Fail

The Industrial Revolution wasn’t powered by a sudden surge in human intelligence. It was powered by the radical notion that maybe, just maybe, the person who solves a problem should benefit from solving it.

Sounds obvious now. Took us ten thousand years to figure out.

But here’s what’s less obvious: rewarding success wasn’t enough. The societies that actually progressed fastest weren’t simply those that made winners rich. They were those that made it survivable to lose.

The Second Unlock: Making Failure Non-Fatal

Britain’s Industrial Revolution happened partly because of patents and markets, yes, but also because Georgian England was an absolutely glorious mess. Bankruptcy laws evolved to give entrepreneurs second chances rather than debtor’s prison for life. Social mobility meant your children weren’t doomed by your failures. Rapid urbanisation created spaces where people could experiment outside traditional hierarchies. The whole system was chaotic, unfair, and frequently appalling, but it was chaos that allowed experimentation.

Compare this to societies with similar technical knowledge where progress remained slower. Guild systems protected established producers from competition. Imperial examination systems funnelled talent toward bureaucracy rather than commerce. Social hierarchies meant failure could taint your family for generations. Innovation required not just possible reward but tolerable risk.

This is why simply having the knowledge wasn’t enough. You could explain steam engines to anyone. But you needed societies where someone could try to build one, fail at building it, learn from the failure, and try again without being utterly destroyed.

Most societies didn’t have this. And so, most societies didn’t progress.

The Third Wave: The Catch-Up Model

By the mid-20th century, Japan discovered what looked like a cheat code. Why endure all that messy trial and error when you could simply identify what works elsewhere, acquire it, and then make it better?

The model was elegant. Study proven technologies. License them or reverse-engineer them. Improve them through disciplined engineering. Manufacture them with obsessive quality control. Minimise risk through exhaustive planning and consensus decision-making.

It worked brilliantly. Japanese companies mastered transistor radios, then televisions, then automobiles, then semiconductors. By the 1980s, Western consultants were frantically trying to copy Japanese management techniques. The future seemed obvious: the efficient, organised, consensus-driven model would triumph over Western chaos.

South Korea, Taiwan, and Singapore ran variations on the same playbook. Korea built massive conglomerates that coordinated entire industries. Taiwan became the world’s workshop. Singapore created a managed economy that attracted multinationals whilst keeping tight control. Each achieved remarkable growth by being extraordinarily good at catching up.

Notice the pattern? They were always chasing something. The technological frontier existed elsewhere, and the path to it was clear: copy, refine, perfect, scale. No need for wild experimentation when you’re following a proven map.

This worked right up until they reached the edge of the map.

Japan’s economy has been essentially stagnant for thirty years. Not collapsing (Japanese trains still run perfectly on time, Japanese manufacturing is still superb, Japanese society remains orderly and functional). But something is missing. The breakthrough innovations that define new industries come from elsewhere.

When the internet emerged, Japan’s corporate culture couldn’t figure out what to do with it. When smartphones arrived, Japanese handset makers, despite technical excellence, were destroyed by Apple and Samsung. In AI, biotechnology, and software platforms, Japanese companies are rarely leaders. The nation that once looked unstoppable is now playing catch-up again.

This isn’t about intelligence. Japanese students consistently outperform Western peers on standardised tests. It’s not about work ethic (Japanese dedication is legendary). It’s about what happens when you propose something genuinely new.

In a system optimised for refinement and risk minimisation, radical ideas die. An engineer who champions an unproven concept that fails may never recover professionally. A startup founder who goes bankrupt faces social stigma that lasts years. The rational choice is obvious: perfect what exists rather than gamble on what might be.

There’s a deeper cultural dimension at work here. The shame-based, collectivist cultures that dominate much of East Asia create powerful disincentives for individual risk-taking. Failure doesn’t just affect you; it reflects on your family, your university, your company, your entire social network. In Japan, this manifests in consensus-driven decision-making where nobody wants to be the person whose idea failed. In Korea, it shows up in hierarchical corporate structures where challenging established thinking can end careers. China managed to partially circumvent this through Communism’s suppression of traditional Confucian hierarchies, but the old patterns remain just below the surface, minus the most extreme expressions. The cultural weight of collective shame makes frontier exploration psychologically expensive in ways that purely economic analysis misses.

The same pattern appears across Asia’s industrial miracles. South Korea dominates memory chips but didn’t invent the technologies that make them useful. Taiwan manufactures the world’s most advanced semiconductors but designs few of them. Singapore hosts pharmaceutical research but hasn’t produced a biotechnology revolution.

Excellence at optimisation, paralysis at exploration.

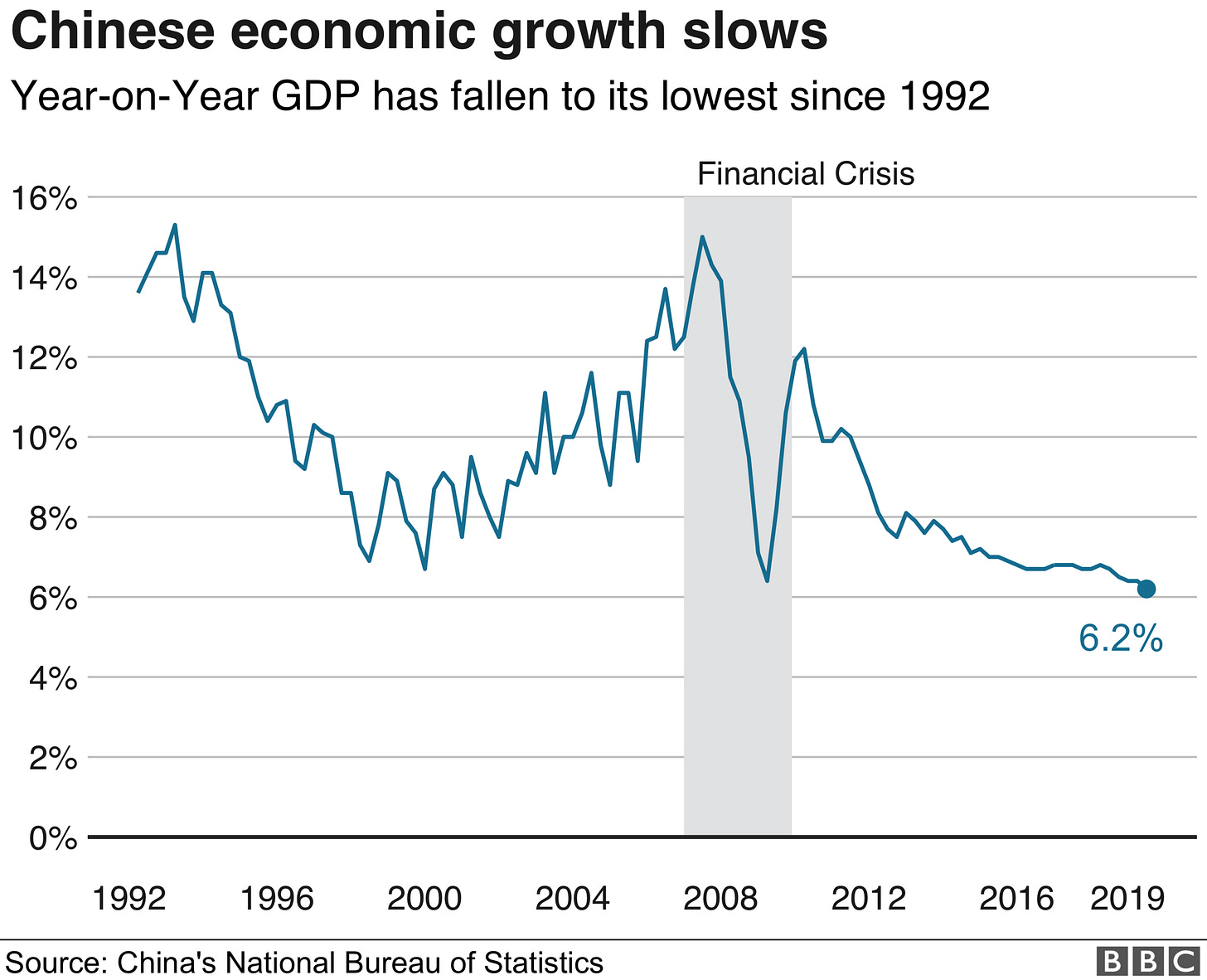

China’s Great Experiment

China is testing whether sheer scale and directed purpose can overcome these limitations. The government pours resources into strategic technologies. Chinese researchers publish prolifically. Chinese companies dominate electric vehicles and battery technology. In certain domains: facial recognition, infrastructure, manufacturing - China leads.

But here’s the uncomfortable question: can you innovate at the frontier when experimentation has political boundaries?

After the 2021 crackdowns on technology companies, the message was clear: innovate within limits, don’t disrupt social stability, remember who’s in charge. For technologies aligned with state priorities, renewable energy, certain AI applications, infrastructure, this works. But for domains requiring genuinely open-ended exploration, where the path forward is unclear and failure rates are necessarily high, do political constraints eventually bind?

The most important innovations are often the ones nobody in power thought to ask for. Nobody directed the invention of the internet, social media, mRNA vaccines, or CRISPR. They emerged from people following curiosity into uncertainty.

China may prove this wrong. The experiment is ongoing. But the historical pattern is concerning: directed innovation works brilliantly for catching up, struggles at the frontier.

The Calibration Problem

Here’s what the past few centuries teach us: progress requires two things in balance.

First, success must matter. People need to capture meaningful benefits from innovation. This is why feudalism failed: no reward, no progress.

Second, failure must be survivable. Most new things don’t work. If attempting something novel means catastrophic personal consequences, rational people won’t try. This is why catch-up economies stall: failure costs too much.

Get the first without the second, and you get sophisticated stagnation - societies with all the knowledge necessary for progress but unable to venture beyond proven concepts.

Get the second without the first, and you get dilettantism - lots of experimentation but no discipline, no follow-through.

Get both, and you get progress.

This isn’t uniquely American, despite Silicon Valley’s mythology. Israel’s startup ecosystem thrives despite, or perhaps because of, existential precocity. Estonia rebuilt itself from Soviet occupation into a digital innovation leader. Switzerland and the Nordic countries balance social safety nets with entrepreneurial dynamism. Britain, despite Brexit chaos and economic struggles, continues producing scientific breakthroughs.

What these diverse societies share isn’t capitalism or democracy or individualism. It’s a cultural and institutional tolerance for productive failure. People can afford to be wrong without being destroyed.

Why This Matters Now

And this is where we need to pay attention, because the stakes are rather higher than they’ve ever been.

Climate change isn’t going to be solved by incrementally better solar panels. We need breakthrough energy storage, carbon capture that actually works, perhaps fusion power, and almost certainly technologies we haven’t imagined yet. The known solutions are insufficient. We need people trying things that probably won’t work.

Declining birth rates are about to collapse pension systems across the developed world. Japan’s population is projected to halve by 2100. China’s working-age population is already shrinking. Europe faces demographic catastrophe. We need radical rethinking of social organisation, economic structures, perhaps even human biology. Tinkering won’t cut it.

Antibiotic resistance is quietly advancing. We’re running out of drugs that work, and the pharmaceutical industry has mostly abandoned antibiotic research because it’s unprofitable. We need new approaches to bacterial infections, possibly abandoning antibiotics entirely for something we haven’t invented yet.

Artificial intelligence might be the most important technology humans ever create, and we have perhaps a decade to establish whether it’s going to be beneficial or catastrophic. This requires experimentation, but also wisdom, but also speed. The combination is extraordinarily difficult.

Inequality is reaching levels that historically precede either revolution or social collapse. We need innovations in education, economic structures, perhaps the fundamental organisation of work. The current trajectory is unsustainable.

None of these problems will be solved by doing what we already know how to do, just more efficiently. They require ventures into genuine uncertainty. And ventures into uncertainty require accepting that most attempts will fail.

This is spectacularly bad timing for humanity to become risk-averse.

The Creeping Sclerosis

Here’s the deeply uncomfortable bit: every successful society eventually develops institutions designed to protect what’s been built, and these institutions gradually strangle the experimentation that made success possible.

Regulations proliferate to prevent catastrophes, but they also prevent experiments. Professional licensing protects consumers but restricts entry. Safety standards ensure quality but increase the cost of trying new approaches. Labour protections provide security but reduce flexibility. Each makes sense individually. Collectively, they calcify.

Even attitudes shift. A generation that struggled up is comfortable with failure because they’ve survived it. Their children, growing up securely, become risk-averse because failure threatens something they already have. Success breeds caution.

This is happening across the developed world. Educational debt makes experimentation financially terrifying for young people. Housing costs force risk-averse career choices. Occupational licensing restricts entrepreneurship in countless fields. The cost of failure rises whilst tolerance for it weakens.

America, despite its rhetoric, shows worrying signs. Healthcare tied to employment makes it harder to found a startup. Student loans create debt peonage. Rising inequality means failure has catastrophic consequences for more people. The freedom to fail is becoming a luxury of the already wealthy.

Europe has generous social safety nets but increasingly sclerotic economies. Asia has caught up to the frontier but struggles to push beyond it. Nobody has solved the calibration problem perfectly, and most successful societies are drifting toward excessive stability.

If all successful societies, regardless of starting point, gradually optimise toward stability and away from experimentation, human progress doesn’t end with catastrophe. It ends with comfortable, efficient stagnation whilst unsolved problems compound.

The Essential Question

We don’t have time for comfortable stagnation.

Climate change, demographics, antibiotic resistance, AI alignment, inequality, these aren’t abstract challenges for future generations. They’re happening now, accelerating, and the window for solutions is closing. We need breakthrough innovations urgently, which means we need people attempting things that will probably fail.

The competition isn’t really between systems or nations. It’s between humanity’s capacity for innovation and the timeline of problems we’ve created. And we’re losing.

The societies that maintain the freedom to fail—that keep the cost of experimentation tolerable, that fund attempts at solving hard problems even when most attempts fail, that create conditions where people can try, fail, learn, and try again—those societies will generate the innovations we desperately need.

The societies that optimise for stability, efficiency, and risk minimisation will produce excellent incremental improvements right up until the compound problems become unsolvable.

For ten thousand years, we didn’t progress because innovation brought no reward. We’ve spent the past few centuries proving that when success is rewarded and failure is survivable, humans can accomplish extraordinary things. The question now is whether we can maintain these conditions whilst solving problems more urgent and complex than any our species has faced.

The irony would be almost funny if it weren’t potentially catastrophic: we finally escaped feudal stagnation by creating systems that tolerate failure, and now, just when we most need people taking risks, we’re making failure unaffordable again.

We need to fix this. Not because innovation is inherently good, but because the alternative, playing it safe whilst problems compound, is civilisational suicide with excellent manufacturing quality and perfectly running trains.

The greatest innovations in human history came from people who tried things that probably wouldn’t work and failed repeatedly before succeeding. We need more of those people, not fewer. We need them trying more things, not fewer. And we need societies that make this possible rather than punishing it.

Because the problems ahead don’t care about our risk tolerance. They’re coming anyway. And solving them will require exactly the kind of messy, uncertain, frequently-failing experimentation that makes cautious societies deeply uncomfortable.

Tough. We’re out of time to be comfortable.

☕ Love this content? Fuel our writing!

Buy us a coffee and join our caffeinated circle of supporters. Every bean counts!

As usual Cymposium, a lot of information in a tight space! I’m optimistic about fusion (the enthusiasm of the ignorant no doubt) simply because the pay-off is so huge (think of the geo-political implications).

I’d argue that China is innovative in certain fields (its emergence in pharmaceuticals is quite something) but not genuinely transformative.

Israel is as ever an interesting case (20% of its GDP is “tech” of one sort or another), but it doesn’t have the multi-billion investment possibilities to fund the LLMs unlike the Gulf (who probably don’t have the talent).

You begin with a serious fallacy: “work yourself to exhaustion, produce barely enough to survive, die young, repeat.”

This is the Hobbesian argument most frequently used to justify feudalism and capitalism - the idea that life was short and brutish before the rise of ownership and industry, and that the current system is the only proper corrective.

In fact, early agrarian and gatherer societies, especially in the fertile areas where they emerged lived in relative abundance. Even the average medieval peasant worked fewer hours than we do now. Life wasn’t necessarily short either, as this confuses mean and average (childbirth and high infant mortality skew the average.)