The Curious Case of America’s Productivity Superpower

The Productivity Gap: A Transatlantic Mystery

America’s economic strength depends on industry’s ability to improve productivity and quality and to remain on the cutting edge of technology

-Ronald Reagan, 40th POTUS

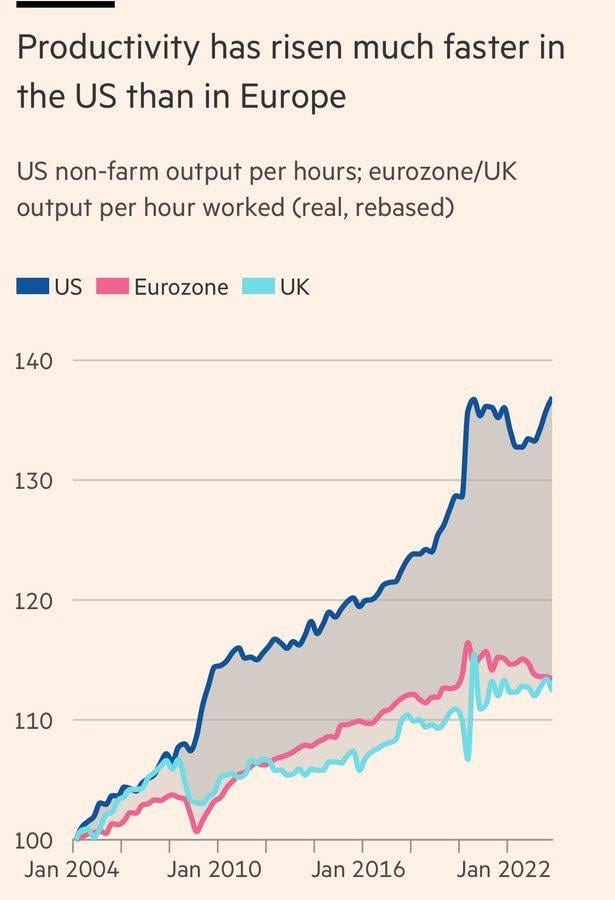

It’s an economic whodunit: Why does the United States seem to outshine Europe (and other Western economies) in productivity? On paper, American workers churn out more GDP per hour than their European counterparts, and that gap has been growing. In 1995, output per hour was about equal on both sides of the Atlantic. One hour of work produced roughly $47 of value in Europe, about the same as in the U.S.. Fast forward to today, and the U.S. leads by over 20% in output per hour. In plain English, the average American worker appears to produce one-fifth more stuff (or value) each hour than the average European worker. This is the puzzle we’re unraveling.

But what is productivity, and why does it matter so much? Productivity is essentially how much output (goods, services, $$) is produced per unit of input (like one worker’s time). A common measure is GDP per hour worked – consider how much value one worker generates in an hour. Higher productivity means more bang for each buck of effort. And as the economist Paul Krugman famously quipped, “Productivity isn’t everything, but in the long run it is almost everything.” A country’s ability to improve living standards “depends almost entirely on its ability to raise its output per worker”. In other words, productivity is a big deal: it underpins higher incomes, better living standards, and economic clout. If the U.S. worker can produce more per hour, the U.S. can grow richer faster than places where workers produce less per hour.

So, if Americans are apparently so much more productive, we have to ask: why? Is Joe in Ohio really doing more in a day’s work than Johann in Germany or Jean in France? Or is something else going on with the numbers? Let’s play economic detective and examine a few prime suspects behind the U.S.–Europe productivity gap.

Suspect #1: Superstar Tech Titans Pumping Up GDP

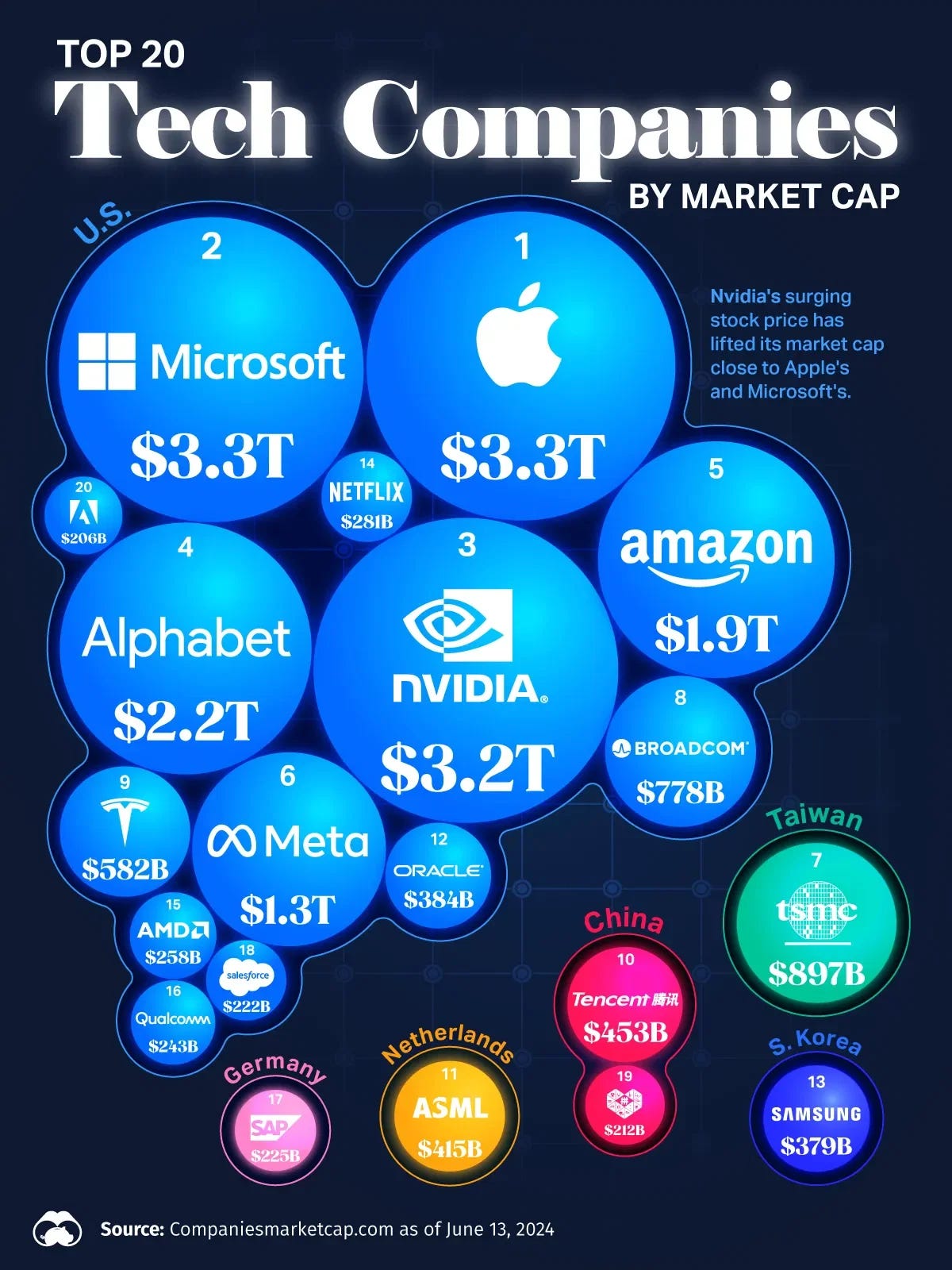

One theory points the finger at America’s “superstar” tech firms – those massive companies whose names you know by heart: Google (Alphabet), Apple, Amazon, Meta (Facebook), Microsoft, Tesla, and friends. These companies are giants not just in tech, but in the entire economy. They rake in enormous profits and contribute heavily to U.S. GDP. However, their services are used globally, not just by Americans. This means a lot of the value they create is enjoyed by people in Europe and elsewhere, but the profits (and measured output) mostly show up in U.S. economic stats. It’s as if the U.S. gets credit for running the world’s tech engine.

To grasp their sheer scale, consider this: the seven largest U.S. tech companies (sometimes dubbed the “Magnificent Seven”) have a combined market value around $12 trillion, roughly equal to the entire GDP of Germany, France, the UK, and Italy combined! In contrast, Europe’s seven largest tech firms are worth only about $0.7 trillion – twenty times smaller. And in the past year, those top American tech firms generated an astonishing $1.72 trillion in revenue, versus a mere $133 billion for the top seven European tech companies. The disparity is mind-blowing.

Real-world examples drive it home. Remember Finland’s Nokia – the king of mobile phones in the 1990s? In 2000, Nokia was worth 15 times more than Apple. Today, Apple’s market value is over $3 trillion, making it 175 times larger than Nokia. Apple’s iPhones, sold to consumers worldwide (Europe included), largely count as Apple’s (and thus the U.S.) output and profits. Europe buys the iPhones; America books the profits. Likewise, in the auto industry, electric carmaker Tesla now boasts a market capitalization over 10 times that of Germany’s Volkswagen (VW). Tesla’s cars are driven from California to Copenhagen, but the company’s value (and much of its production value-add) inflates U.S. economic metrics, not Europe’s.

In short, America’s productivity numbers get a big lift from a handful of superstar firms that dominate globally. Europe, meanwhile, has fewer such giants. (As one report noted, Europe has only a handful of companies valued over $100 billion, whereas the U.S. has dozens.) Though vibrant in spots, the EU’s tech sector hasn’t (yet) produced an Apple or Google equivalent to boost its GDP. So, when you see U.S. productivity stats, a chunk of that reflects Big Tech’s global gravy train flowing into U.S. accounts. It’s less than every American worker is a super-producer, and more that America has more super-producing companies. These “superstar” firms can make the nation’s averages look higher (that’s why we look at medians instead of averages).

Suspect #2: Energy – America’s High-Octane Habit

Another theory highlights an old-school factor: energy. The U.S. uses much more energy per person than Europe, which can juice output (at least the kind of output GDP measures). Think of an economy like a machine – feed it more fuel, and it can crank out more power. Americans burn a whole lot of fuel. How much more? On average, an American uses over 6.5 tons of oil-equivalent energy per year, more than double the energy consumption of the average EU resident (about 2.8 tons). Whether it’s electricity, gasoline, or natural gas, by almost any measure, per-capita energy use in the U.S. is vastly higher. When comparing the U.S. and EU, the energy used per worker is nearly twice as high in America.

What does guzzling energy have to do with productivity? Well, energy is an input to production. Abundant cheap energy can boost output: factories run full tilt, big box stores stay open 24/7 under bright lights, and millions of trucks crisscross the country moving goods. The U.S. has historically enjoyed lower energy prices and higher usage – think of widespread air conditioning, countless gas-guzzling SUVs, and power-hungry server farms. All that energy consumption shows up as economic activity (more driving = more gas sales, more AC = more electricity generation, etc.), padding the GDP. Europe, by contrast, taxes energy heavily and tends to be more frugal with it.

There are also practical reasons why Americans use more energy. The U.S. is geographically large and less densely populated, so people often commute longer distances by car (burning fuel). Many American cities are built for automobiles and suburbia, whereas Europeans more often use public transport or live in compact cities. Additionally, the U.S. spans regions with extreme climates – scorching summers in Texas, freezing winters in Minnesota – leading to heavy use of heating and cooling. Europeans, blessed with milder overall climate and efficient transit, simply don’t need to consume as much energy for the basics. But in GDP terms, a higher energy bill can look like higher output.

The upshot: part of America’s higher output per person might not reflect greater efficiency, just greater energy input. It’s as if the U.S. economy is a muscle car with a massive engine – high fuel intake, high horsepower. Europe is more like a fuel-efficient sedan – sipping energy and getting good mileage, but ultimately recording less total output because it’s burning less fuel. This raises an interesting question: Is the American worker truly more productive or just backed by more machines and energy? If you give two farmers different tools – one a hand plow and the other a tractor – the one with the tractor will plow more fields in a day. In this analogy, the U.S. workforce has many “tractors” (literal and figurative) at its disposal.

Suspect #3: Financial Wizardry and Real Estate Magic

Our next suspect hides in plain sight on Wall Street. The U.S. economy is highly financialized, meaning finance and real estate loom large in the GDP figures. Critics argue that America’s stellar productivity stats are puffed up by financial sector profits and a booming real estate market, which may not reflect proportional gains in “real” economic value. In simpler terms, pushing money around can generate much measured output (and wealthy bankers), but does it make the average worker more efficient at making tangible products? Unclear. It does, however, make the GDP pie bigger – and with it, productivity if measured as GDP per worker.

Let’s look at some numbers. The finance, insurance, and real estate sectors (together known as “FIRE”) make up a much larger share of the U.S. economy than they do in Europe. Over the past few decades, this share has ballooned. Between 1979 and 2005, the FIRE sector’s contribution to U.S. GDP rose from about 15% of the economy to over 20%, and it has remained substantial since. Today, roughly a fifth (or more) of American economic output comes from these sectors. For context, that’s about the same portion of GDP as the entire manufacturing sector in the U.S. In Europe, economies tend to be relatively less dominated by finance/real estate (though the UK is a bit of an outlier).

What does it mean that finance/real estate count for so much? Consider real estate: when property values and rents rise, it boosts GDP (via higher construction output, real estate services, etc.). The U.S. has seen enormous housing and commercial real estate booms in recent decades. Europe, with stricter zoning and in some cases slower growth, has a smaller real estate footprint in GDP. Finance is even more telling. American financial institutions are giants by global standards. For example, JPMorgan Chase, one single U.S. bank, recently hit a market capitalization of about $675 billion, greater than the combined value of the ten largest banks in Europe (around €513 billion for all ten!). That’s one bank outweighing an entire continent’s banking sector. U.S. banks and investment funds also generate hefty profits (which count as GDP). In fact, at times, the financial sector has earned around one-half of all U.S. corporate profits, much of it through trading, fees, and speculative investments. All of this inflates the U.S. economic output numbers, even if it’s not directly making workers on the factory floor more efficient.

To make this more concrete, think of Wall Street vs. Frankfurt. New York’s financial district mints billionaires and IPOs like it’s going out of style – all that finance activity shows up as value-added in U.S. GDP. Frankfurt (one of continental Europe’s finance hubs) is staid by comparison; Europe’s banks often play second fiddle and face stricter regulations. The risk-taking, high-flying financial culture in the U.S. pumps up profits and salaries in finance. It’s great for GDP figures when a hedge fund makes a killing or when Goldman Sachs underwrites a huge deal – but it doesn’t necessarily mean the U.S. worker learned to build cars 10% faster on average. It’s an important distinction: measured productivity can rise if lucrative sectors grow, even if most workers aren’t personally producing more than before.

In summary, America’s larger finance and real estate sectors act like a statistical mirage, boosting output per worker on paper. If a greater share of your economy comprises high-dollar financial transactions and pricey real estate deals, your average GDP per person will look higher. Europeans might be making plenty of valuable things, but fewer are day-trading or flipping real estate at the scale Americans do.

Other Accomplices: Culture, Policy, and Demographics

Beyond our three prime suspects, other factors could help crack the case of the productivity gap. These are more qualitative but still vital in understanding the big picture:

Labor Laws and Work Culture: The U.S. labor market is relatively flexible – hire and fire is easier, and long hours or limited vacation are common. Conversely, Europe has stronger worker protections, generous vacations, and often shorter workweeks. This affects productivity metrics in a couple of ways. First, Americans tend to work more hours per year than many Europeans (who enjoy August off or a 35-hour workweek in France). Working more hours doesn’t raise hourly productivity but boosts GDP per capita. Second, some argue that Europe’s strict labor laws can reduce dynamism – firms might be cautious about hiring or may hang onto less productive roles due to regulations, whereas American companies more readily shed or reinvent jobs to maximize output. However, Europe’s approach also means less burnout and perhaps workers who are more productive during the slightly shorter time they do work. It’s a trade-off. Notably, Europe’s economic challenge “is not about working longer hours or taking shorter holidays but improving the amount of value-added” per worker. In other words, Europeans shouldn’t simply work more; the focus is on making each hour count for more, which circles back to innovation and efficiency.

Risk Appetite and Innovation Ecosystem: The U.S. has a well-known culture of entrepreneurship and risk-taking. Silicon Valley’s mantra of “move fast and break things” exemplifies a tolerance for failure in pursuit of big breakthroughs. This dynamic environment, bolstered by deep venture capital pools, helps spawn superstar firms (our Suspect #1) and keeps incumbents on their toes. Europe has great innovators too, but historically the venture capital investment in the EU has been far lower (as a share of GDP) than in the U.S. Turning startups into “unicorns” – billion-dollar companies – has been an American forte. The market dynamism in the U.S. (fast business creation and destruction) reallocates resources to productive firms quickly, whereas Europe’s more regulated markets can be slower to churn. This may mean the U.S. economy is quicker to adopt new technologies or business models that raise productivity, while Europe sometimes lags in diffusion of innovations. Think of how swiftly Uber or Airbnb spread in the U.S., versus the greater regulatory resistance they met in some European cities.

Demographics and Workforce: Demography is destiny, they say. The U.S. has a younger and faster-growing population than many European countries, partly thanks to higher immigration. A growing workforce can boost GDP, but what about productivity? Younger economies might be more willing to embrace change and have a larger share of workers in tech-savvy ages. Europe’s population is older on average, and some countries are shrinking. This can lead to a smaller labor force and potentially less dynamism. However, older workers can be very productive too – experience matters – so the link isn’t straightforward. One demographic advantage the U.S. has is attracting top global talent. The U.S. famously sucks in skilled immigrants (from software engineers to scientists) – about 40% of OECD skilled migrants reside in the U.S. – which expands the pool of innovators and high-productivity workers. Europe is catching up in this regard, but historically hasn’t been as open or attractive to global talent across the board.

Regulation and Market Size: The European Union is a single market in theory, but in practice it’s more fragmented than the U.S. There are different languages, regulations, and consumer preferences across 27 countries. This can hinder a firm’s ability to scale up quickly in Europe – what works in France might need tweaking in Sweden or Spain, and there may be more hoops to jump through to expand. The U.S., by contrast, is a giant homogenous market in many industries, allowing companies to achieve massive scale at home. As one central banker noted, high-productivity European firms have a harder time scaling up to U.S. size due to these frictions, which ultimately lowers aggregate EU productivity relative to the U.S.. Moreover, Europe tends to regulate more tightly in areas like antitrust, privacy, and worker rights. While this can protect consumers and workers (arguably a good thing), it might also slow down some business practices or technologies, at least initially. The U.S. has historically been more laissez-faire until problems emerge. You could say Americans let industries run wild a bit (whether it’s ride-sharing or biotech) which can boost productivity, whereas Europeans take a more cautious approach that sometimes trades a bit of efficiency for other social values.

All these factors—cultural, political, structural—add texture to the productivity story. They’re like supporting characters in our mystery, making the plot more complex. The result is an environment in which the U.S. has, for decades, managed to eek out more economic output growth than many of its peers.

Europe’s Productivity Mirage: An Open-Air Museum in the Making

Let’s stop squinting at the numbers as if this is a photo-finish. In the hard metrics that decide economic heft—GDP per capita, venture capital, market-cap heavy-hitters—the EU isn’t merely behind the United States; it’s falling off the back of the peloton. The average European now produces barely half the output of an American (EU GDP per capita has slid from 76 % of the U.S. level in 2008 to just 50 % in 2023). That 50-point gap isn’t a rounding error; it’s an indictment.

The picture is even uglier in the industries that mint tomorrow’s wealth. Of the world’s 50 biggest tech firms, a risible four carry an EU passport. Venture capital tells the same story: in 2024, U.S. startups hoovered up $209 billion, while the entire continent scraped together a shrinking $62 billion—one-third the U.S. haul and down year-on-year. Europe isn’t “catching up”; it’s financing Silicon Valley’s next sprint.

Why? Because Brussels has engineered a perfect cocktail of stagnation: sky-high energy prices (industrial power costs run two-to-three times U.S. levels), a demographic cliff that will see the working-age population shrink in 22 of 27 member states by 2050, and a regulatory reflex that treats every new technology as a threat needing pre-emptive strangulation. The AI Act, the GDPR bureaucratic maze, the fragmented capital markets—each is a brick in the wall keeping entrepreneurs on the other side of the Atlantic.

Yes, Europeans still enjoy postcard villages, six-week holidays and museums stuffed with Renaissance loot. Lovely. But culture doesn’t pay pension checks, and a welfare model built for the 1980s cannot survive when the tax base is aging faster than the frescoes. “Quality of life” without productivity is just a slow-motion liquidation of inherited capital.

Meanwhile, America is compounding. It draws global talent, writes the software, designs the chips, and—crucially—keeps the upside. Europe debates whether an algorithm’s training data hurt someone’s feelings; the U.S. ships the product and collects the cash. That is why the scoreboard keeps tilting westward.

So let’s call it: in the race that matters, the EU is drifting toward curated irrelevance—a lifestyle superpower and economic lightweight, the world’s nicest retirement home subsidised by past glories. If Brussels wants a future that isn’t scripted by Washington (or Beijing), it needs less sermonising, cheaper energy, unified capital markets, and the humility to admit the U.S. model is winning. Otherwise, the Old Continent will remain just that—old, scenic, and economically irrelevant.

☕ Love this content? Fuel our writing!

Buy us a coffee and join our caffeinated circle of supporters. Every bean counts!

There is one very boring, but nonetheless important, factor I feel you left out, and that is supply chain speed and efficiency. As someone who works in manufacturing, I have to say it is hard to overstate what a huge difference this makes. In the US (and to be fair manufacturing centers in China as well), if you break a tool, or need supplies, or have to get a replacement part, you go on a website, order what you need, and it will either be here tomorrow, or if you need it faster than that, you can often drive over to the warehouse and pick it up today.

In most other countries it just doesn't work that way. You have to contact your dealer, who may or may not have an up to date inventory on their website. You tell the sales rep. what you need, and they will get back to you with a quote, which will probably take at least a day, maybe as much as a week to get. Then you approve the quote. They send the order to their distributior, and then they give you an ETA of when you can expect it. All in all, something that is one or two days in the US, can end up taking weeks in many other countries.

This might sound like a simple inconvenience, and not something that is going to make a major difference in GDP, but if you are prototyping a new product, or running a job shop that handles multiple customer orders, this simple issue can dramatically lengthen time tables on production. A project that could realistically a week to turn around a prototype with a modern, responsive, supply chain, can easily stretch out to several months if you have to wait for parts and supplies. Spread that out over the entire economy, and it is a measurable hit to overall productivity.

Wait... so first you explain how American GDP is a one giant dot.com bubble...and then you claim EUR is "falling off"? It reminds me of articles about 10 yrs ago describing how "rich" Russia is because of its GDP growth. Pathetic.