Urgent Repair Needed: The NHS

A Comprehensive Reform Framework for a once proud and enviable but now ailing healthcare system

Leaving the broken system the way it is, that’s not a solution

-Barack Obama

It was a grey Tuesday morning when I found myself waiting in A&E for 11 hours with persistent pain. I sat in a corridor alongside dozens of others, all of us watching staff rush past, clearly doing their best despite impossible demands. Three months later, when I finally saw a specialist, I learned I needed treatment. "The waiting list is about 9 months," the consultant explained calmly. What followed was a frustrating maze of postponed appointments, lost referrals, and hours spent on hold trying to navigate the system. This isn't some rare experience; it's become the ordinary reality for many patients across Britain.

Yet it wasn't always this way. The NHS was born in 1948 from the rubble of post-war Britain, when the country was literally in ruins. Despite these challenges—or perhaps because of them—the government of the day understood that a healthy population was essential for rebuilding the nation. Aneurin Bevan's vision of healthcare free at the point of use revolutionised British society. No longer would people suffer without treatment because they couldn't afford medical help. The NHS touched and uplifted millions of Britons, from the exhausted post-war generation through the economic boom years, becoming not just a health service but a cornerstone of national identity.

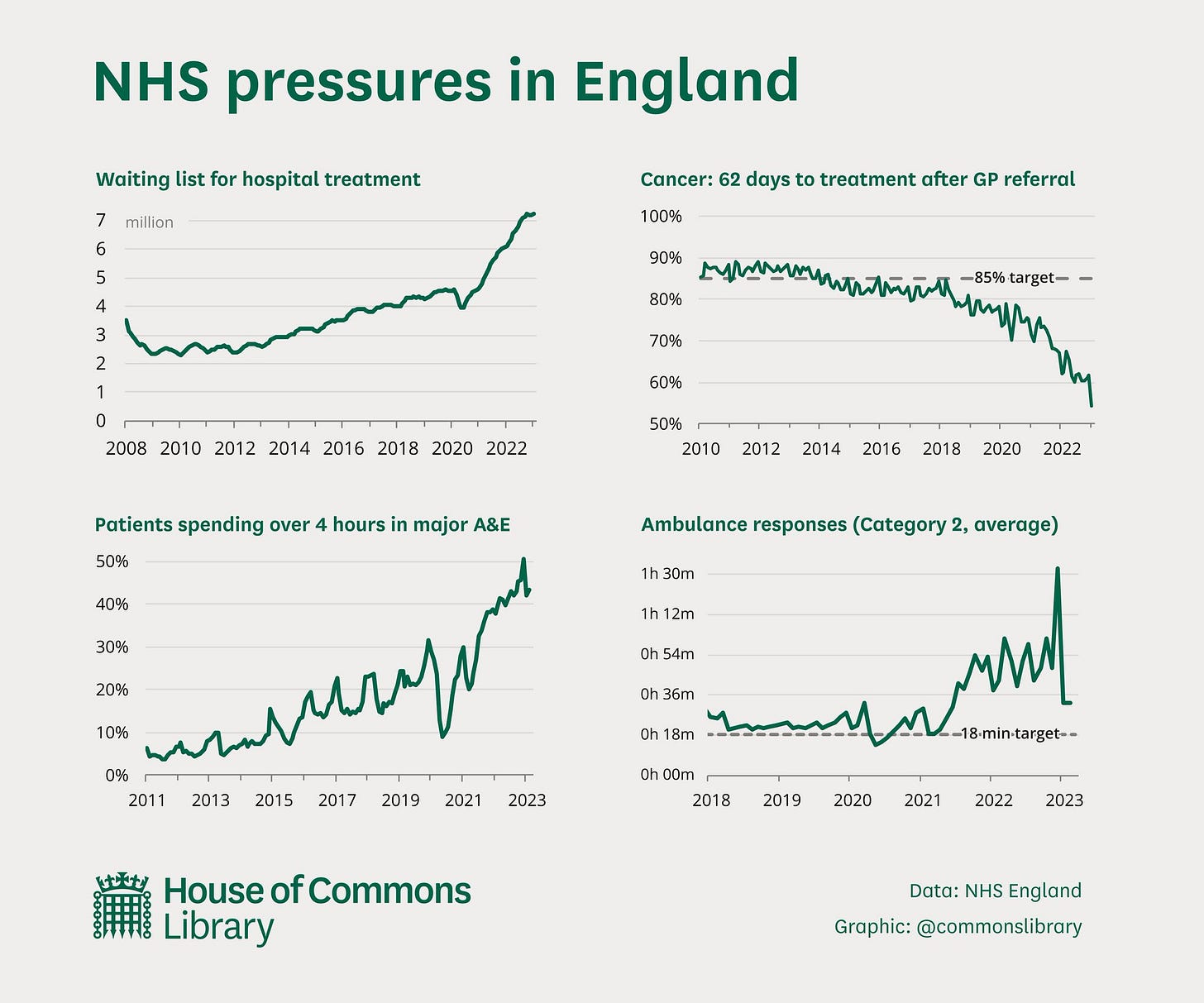

The first serious cracks began appearing in the early 2000s. Initially, they were almost imperceptible—slightly longer waiting times, occasional staffing shortages, administrative complications. By 2008, with increasing pressure on public services, these cracks widened. Politicians promised "efficiency improvements" that, in reality, meant stretching resources further. The 2012 Health and Social Care Act introduced structural reforms that fragmented services while claiming to improve them. Gradually, the NHS transformed from a national treasure to a national concern, with winter crises becoming an annual tradition as predictable as Christmas.

The National Health Service stands at a critical juncture. For 75 years, the NHS has embodied our national values of equality of care and equity of access. However, today's reality reveals a system under unprecedented strain—with overloaded hospitals, patchy care access across regions, insufficient preventive health measures, and a workforce feeling undervalued and overworked.

We're practicing corridor medicine now. It's become normal to have patients waiting 24-48 hours for a bed. That's not healthcare—that's warehousing the sick.

- An emergency medicine consultant, speaking anonymously

This crisis demands more than piecemeal solutions. It requires bold, systematic reform that acknowledges the scale of our challenges while building on the NHS's considerable strengths. Most importantly, any meaningful change must be clinician-led, patient-validated, and politically facilitated—not imposed from the top down.

Confronting the Scale of the Challenge

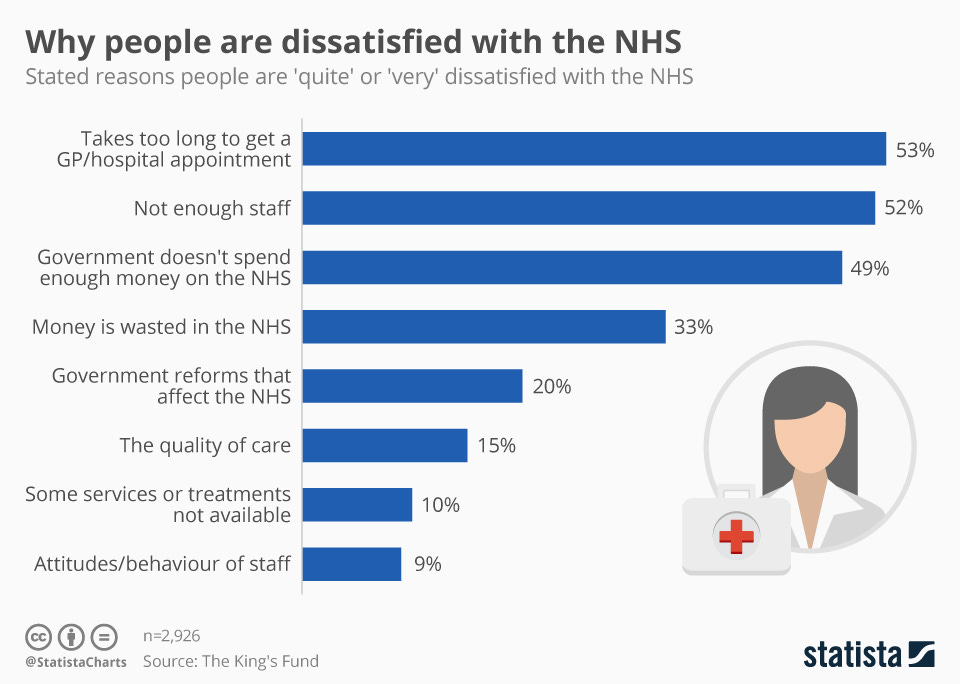

The first step in fixing the NHS is acknowledging the true extent of its problems. The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated existing pressures but did not create them. Today, we face:

Record waiting lists for elective care

Severe problems with primary care access

Dangerous delays in emergency care

Chronic workforce shortages across all healthcare settings

Outdated infrastructure and inefficient processes

Increasingly normalised substandard care

While these challenges are serious, context matters. Compared to other socialized healthcare systems, particularly those in Eastern Europe, the NHS still delivers reasonable outcomes. Poland's public healthcare system faces waiting times that can stretch into years for some specialists, while Romania struggles with severe rural healthcare deserts. Even France and Germany, often cited as exemplars, have their own access issues and funding crises.

Many countries have responded to similar pressures by adopting hybrid approaches. Singapore combines universal coverage with mandatory savings accounts and co-payments. Australia maintains a public system while incentivizing private insurance through tax benefits. Sweden allows private providers to compete for public funding. These hybrid models preserve universal access while introducing elements of market competition and personal responsibility to address efficiency and funding challenges.

The real danger we face is the growing acceptance of unacceptable standards. What was once considered intolerable is increasingly met with the fatalistic attitude that "that's just how it is now." Breaking this cycle requires honesty about where we stand and a comprehensive strategy for where we need to go—one that acknowledges both the NHS's relative strengths and the successful innovations seen in other healthcare systems.

A Six-Point Plan for NHS Transformation

Drawing from the expertise of healthcare professionals, here are six critical steps that would transform both performance and public perception of the NHS:

The new Labour government has put out their own mandate called the “road to recovery”

1. Link Primary Care to Social Care and Redefine GP Roles

Primary care desperately needs improvement and integration with a revamped social care system. We should consider establishing a new institution—NHS-Community—with its own dedicated budget. This would allow GPs to:

Facilitate hospital discharges

Lead care in the community, including community hospital beds

Focus on complex illness management and medication decisions

Reduce administrative burdens (currently 50-70% of GP time)

Coordinate community care effectively

The boundaries of GP work need fundamental redefinition. GPs should not be expected to fulfil family doctor and secondary-care gatekeeper roles while also handling screening and administrative tasks that could be managed by others or streamlined with better IT systems.

Any changes to GP roles must involve the profession itself. Reform cannot be imposed from above. Returning retired GPs to work could provide immediate capacity increases while developing longer-term workforce solutions.

2. Establish Clear National Standards

We need ambitious national healthcare guarantees that reflect what we would want for our own families:

Maximum 48-hour wait to see a healthcare practitioner in primary care

Maximum four-hour waits in A&E

Hospital discharge to community placement within days, not weeks

Addressing the current "postcode lottery" requires UK-wide standards. What's delivered in Tonbridge should be available in Teesside. This necessitates professional triage systems run by trained staff and prioritisation mechanisms similar to those used by ambulance services.

Achieving these standards will likely require redistributing resources and personnel from secondary care towards primary care—a difficult but necessary shift.

3. Transform the Care Profession

Care work must become a respected, sought-after occupation. We can achieve this through:

Tax advantages for care workers

Free travel passes for carers

Improved continuous professional development opportunities

Clear career progression pathways

Better working conditions and pay structures

Valuing NHS staff is crucial for addressing the workforce crisis. Current pressures drive experienced staff to reduce hours, decline additional commitments, or retire early—creating further staffing shortfalls.

4. Revolutionise Preventive Health

The NHS performs poorly on prevention outside of specific cancer screening programmes. We should establish dedicated screening centres providing:

Blood pressure testing

Cholesterol monitoring

Prostate screening for men

Cervical screening, breast cancer and osteoporosis screening for women

These centres could be partially funded through public contributions while maintaining equitable access. We must reject proposals for charging for GP visits, which would create inequalities in care access.

5. Implement an Effective Obesity Strategy

Tackling obesity is key to reducing cardiovascular and cancer mortality. This requires:

Comprehensive diet education programmes in schools

A compulsory GCSE on personal health

Public health campaigns targeting nutritional awareness

Early intervention programmes in high-risk communities

The public health benefits of such initiatives would be enormous within just a few years.

6. Address Mental Health Service Gaps

Mental health requires urgent attention, including:

Improved access to therapy for mentally distressed people

Campaigns to reduce stigma around mental illness

Early intervention for critical life events such as school exclusions

Integration of mental health services with physical healthcare

Preventive approaches focusing on childhood and adolescent wellbeing

Modernising NHS Infrastructure

Beyond these six points, comprehensive reform requires significant infrastructure modernisation:

Digital Transformation

The UK government has committed over £2 billion to upgrade NHS technology, which should support:

Prevention of health and social care needs escalation

Personalised care and reduced health disparities

Improved provider experiences

Effective information-sharing systems throughout patients' lives

Physical Infrastructure

The NHS's physical infrastructure requires substantial investment, particularly in:

Mental health facilities

Primary care premises to accommodate expanding staff teams

Community care settings to support the shift from hospital-centric models

Upgraded hospital facilities to address the maintenance backlog

Resource Allocation and Funding

While fixing the NHS isn't solely about increased funding, appropriate resources are essential. A balanced approach to investment is needed across:

Preventive services that reduce future demand

Primary and community care that manage health issues before hospitalisation

Acute services that deliver specialised interventions when needed

Digital infrastructure that enhances efficiency

Workforce development ensuring adequate staffing with appropriate skills

A Bold Proposal: Clinician-Led Governance Reform

Prime Minister Keir Starmer's March 2025 announcement to disband NHS England (NHSE) creates a crucial opportunity—but only if frontline professionals take the lead in what follows. The disbanding itself isn't the solution; it merely removes an obstacle to meaningful reform.

NHSE's excessive control over NHS trusts has stifled local initiative and innovation. As one hospital chief executive described it, NHSE was "the biggest kiss up, kick down, organisation in public life." While Health Secretary Wes Streeting speaks of "ending the infantilisation of frontline NHS leaders," the real test will be whether those leaders are genuinely empowered or simply subjected to a different form of centralised control.

Patient safety advocates cautiously welcome this change. Dr. Helen Richards, who has campaigned for better maternity care since 2018, notes: "NHSE's safety failures weren't just organisational problems—they reflected a culture that prioritised reputation management over transparency. Dismantling NHSE won't help unless frontline staff can reshape what replaces it."

The East Kent maternity scandal—where at least 45 babies might have survived with better care—showcases the danger of bureaucratic oversight without clinical leadership. Despite awareness of problems since 2013, NHSE's approach was "a pattern of hiring and firing" rather than addressing fundamental clinical concerns.

For this restructuring to succeed:

Clinicians and patients must lead the design of what replaces NHSE

Local clinical teams must have genuine autonomy to respond to community needs

Independent patient advocacy must be truly independent—not controlled by any central body

Transparency must be built into governance, with advance publication of all meeting materials

Professional accountability must replace bureaucratic compliance

Professor James Walker, former clinical director for maternity care at the Healthcare Safety Investigation Branch, emphasises this opportunity: "Throughout the whole of the health service, we've totally lost empathy for the patient. We've become very regimented—we need to focus on how we can help, rather than whether someone fits into a framework."

Dismantling NHSE creates space for change, but without putting clinicians in charge of reform, we risk replacing one bureaucracy with another—simply shifting the furniture while the house continues to crumble.

Conclusion

The NHS faces profound challenges, but with concerted effort, we can create an excellent health service that is internationally acknowledged. Clinicians must devise the path forward, patients must validate it, and politicians and administrators must facilitate—not dictate—it.

By addressing workforce shortages, modernising infrastructure, shifting care models, balancing prevention with treatment, reforming social care, and establishing sustainable funding frameworks, we can honour the NHS's achievements by creating a system fit for the next 75 years.

Failure to act decisively risks a slide toward an American-style healthcare dystopia. Imagine a Britain where your postcode and bank balance determine your chances of survival. Where families crowdfund for cancer treatment. Where ambulances ask for insurance details before loading patients. Where the wealthy access world-class care while others languish for years on waiting lists or forgo treatment entirely. Where a serious diagnosis means not just health concerns but financial ruin. This isn't fearmongering—it's the logical endpoint of our current trajectory if we continue to apply plasters to a system requiring major surgery.

Dr. James Harrison, who worked in both the NHS and American hospitals, puts it starkly: "What I witnessed in the US should serve as a warning. Patients rationing insulin because they couldn't afford it. Families bankrupted by hospital bills. People avoiding preventive care until emergencies forced them into the most expensive interventions. The UK is sleepwalking toward this reality through neglect of the NHS's fundamental problems."

Most importantly, fixing the NHS demands honest recognition of the scale of problems and commitment to action rather than rhetoric. Those best qualified to propose, debate, test and implement reforms must be empowered to lead this transformation.

The NHS was born from a bold vision in 1948. Saving it requires equally bold thinking today.

☕ Love this content? Fuel our writing!

Buy us a coffee and join our caffeinated circle of supporters. Every bean counts!

I believe part of the pressure on A&E stems from the lack of accessible primary care in the community. When it takes two weeks to see a GP or nurse, it's no surprise that people head to A&E just to be seen sooner. I’m not sure why it’s so difficult to establish more Walk-In Centres or to incentivise GPs to offer extended hours, including Saturdays.

Great article - and as a retired GP who left in my mid 50's due to a combination of becoming a carer and burning out, I am interested in how you would 'return retired GP's to practice'. I left feeling disempowered, disillusioned and exhausted and it would take big changes to get me back. There are also many younger GPs who are out of work due to funding being ring fenced for other roles. Giving back the control and funding to practices so they can employ the right people for their teams would increase the number of GPs at the coal face and, more importantly, stop the younger ones from emigrating to countries where the work environment is better for them. And absolutely - as you say - redefining the GP role so they can concentrate on communuty care, holistic care and continuity of care, which is how it felt like it used to be 15 years ago, would be a great start.