DOGE: Necessity or Stupidity?

Exploring whether DOGE works or just another bloated and useless government department

Picture this.

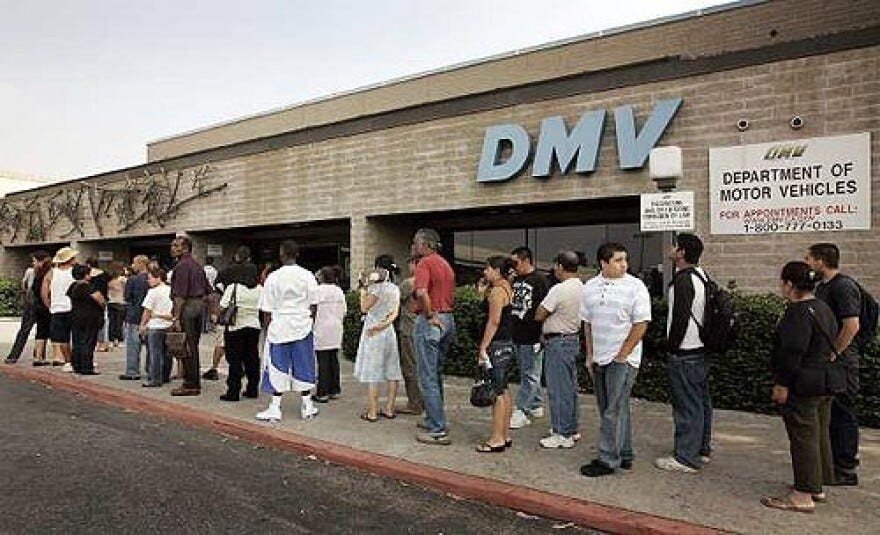

You rise early, determined to outsmart the system. Today, you're going to the Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV) to renew your licence—a dull but necessary civic ritual. You arrive at 7:30 a.m.—smug, even—believing you’ve beaten the rush. But alas, your optimism is misplaced. A crowd has already gathered, groggy and grim-faced, as though queuing for the last lifeboat on a slowly sinking ship.

As the minutes drag by, the line swells. The air thickens with irritation. People shift, sigh, and check their phones with religious devotion. Then, at precisely 8:50 a.m.—twenty minutes before the posted opening time, mind you—two DMV workers saunter down the corridor with the air of runway models doing government chic. All eyes are on them. They know. They don’t care.

They reach their desks. They sit. They stretch. They sip from coffee cups with the theatrical slowness of a French art film. Then, without urgency, they flick the ‘CLOSED’ sign to ‘OPEN’ and give a half-hearted wave to the first in line, as if to say, "Come, peasants, let’s get this over with."

You now notice that while there are ten counters, only two are manned. It’s now 9 a.m. Two people processing an ever-growing mass of increasingly bitter humanity. The line trudges forward with the velocity of tectonic plates.

By 10 a.m., you’re still stuck somewhere between despair and resignation. When you finally arrive at the counter, the clerk glances at your paperwork, grunts, and informs you—with a roll of the eyes that would make a teenager proud—that you’re missing a crucial document. You must return tomorrow.

You stare at them. A fire rises in your chest. You briefly entertain the idea of expressing your dissatisfaction physically. But a glance at the burly security guard polishing his truncheon squashes that fantasy.

And so you leave. Day wasted. Sanity tested. Licence unrenewed.

Sound familiar? Of course it does. Because this isn’t just the DMV, this is the global blueprint of public service misery. Swap out licences for healthcare, and you’ve got a nearly identical scene—this time with slightly more fluorescent lighting and the lingering scent of antiseptic despair.

Imagine walking into a government hospital or clinic—say, the VA. You’re not expecting luxury. You’re not expecting concierge medicine. You just want to be seen. Perhaps you’ve got a lingering pain, a referral letter, or a prescription that’s run out. What greets you is a waiting room that looks like a scene from a Cold War film—flickering screens, battered chairs, and an ancient fish tank with exactly one depressed fish floating at the top.

You approach the front desk. The receptionist is engaged in a high-stakes battle with a stapler. Eventually, they acknowledge you, not with a greeting, but with a form. You fill it out. You wait. And wait. And wait.

Nurses pass by like ghosts in scrubs. A doctor occasionally appears in the distance, like a rare woodland creature, before vanishing behind a door marked “Authorised Personnel Only.” The PA system crackles every so often with an announcement that means nothing to anyone. Hours pass. You’re either forgotten, misfiled, or triaged into a mysterious category called “Come Back Tuesday.”

When your name is finally called, you rise like it’s salvation. The doctor glances at your chart, asks three questions, types for five minutes, and tells you to get more rest and maybe drink more water. You are politely ushered out, bewildered and untreated.

Subpar? That’s the polite version.

From Johannesburg to Jakarta, from Detroit to Delhi, public service facilities around the world share one unifying trait: they are reliably, stubbornly mediocre. Not catastrophically bad—though some come close—but consistently frustrating, inefficient, and soul-draining. They operate on the fumes of outdated systems, chronic understaffing, and a kind of bureaucratic entropy that seems immune to reform.

Cue the present……

One of the first things Donald Trump did when he took office was to create a brand-new government department, boldly named the Department of Government Efficiency—or, amusingly, DOGE for short. (Yes, just like the internet meme. And now a memecoin. You couldn’t make it up.)

To run this new department, Trump appointed his wealthy new pal (not anymore recently), Elon Musk. Now, both Trump and Musk come from the business world—or, more accurately, the private sector—and they’ve always believed that government workers are hopelessly slow and inefficient compared to the go-getters of industry. This rivalry between public and private sectors is well known around the world, and to them, it’s not just an opinion—it’s practically a law of nature.

So, Trump had what he clearly thought was a brilliant idea: bring in Musk, the eccentric billionaire who wants to send humans to Mars and fill the roads with self-driving cars, and put him in charge of telling career civil servants just how rubbish they are at their jobs.

It was, in short, like putting a tech tycoon in charge of a post office and expecting it to run like a rocket launch—grand, absurd, and more than a little entertaining to watch.

Elon Musk is famously—or infamously—a workaholic of near-mythic proportions. The man barely sleeps, owns fewer houses than a retired librarian, and somehow manages to juggle more billion-dollar companies than most people can manage email accounts. Rockets, electric cars, underground tunnels, AI—he’s got a finger in every futuristic pie, all while appearing to defy time, sleep, and fundamental human limits.

So naturally, when Trump needed someone to whip the sprawling beast of the U.S. civil service into shape, Musk seemed like the obvious choice. If anyone could take the most sluggish, bureaucratic machine on Earth and inject it with a dose of Silicon Valley-style adrenaline, surely it would be the man who’s trying to colonise Mars between meetings.

After all, if you want miracles, best call someone who’s already working on them before breakfast.

Let’s take a stroll through some of DOGE’s greatest hits—assuming one counts mass layoffs and bureaucratic bloodletting as chart-toppers.

First up, Musk wielded an AI tool like a digital guillotine, slicing 260,000 federal workers from the payroll. Some were laid off, others gently nudged toward early retirement or bought out entirely. It was efficiency by attrition, and it made a statement: the age of the bloated bureaucracy was over, at least in theory.

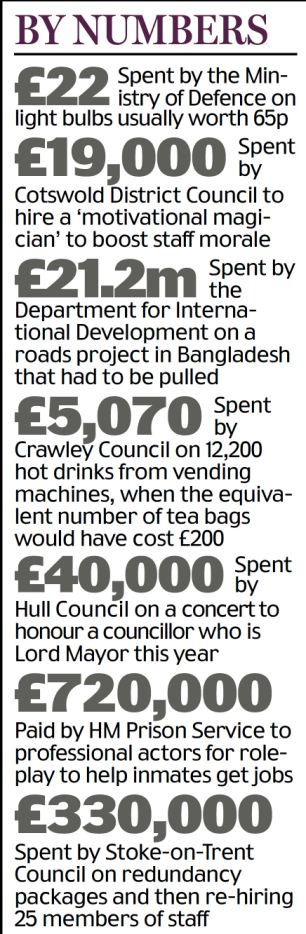

Next came a purge of federal contracts. Out went 9,500 of them, saving a tidy $32 billion. Not exactly pocket change, even for a government with a defence budget that could fund a small planet. Then there were 250 underused property leases—cancelled, trimmed, and tossed in the bin, shaving off another $100 million a year. It’s the kind of move that makes accountants weep with joy and real estate lobbyists reach for their phones.

The Social Security Administration got its own haircut—7,000 positions eliminated in the name of streamlining. As for USAID, the international development agency, it was unceremoniously taken off the chessboard by executive order. Foreign aid? Too slow, too soft, and not terribly profitable. Out it went.

In their place: technology, automation, artificial intelligence. The idea is to replace tired, error-prone human beings with machines that don’t sleep, strike, or surf Facebook and TikTok on government time. And to further lighten the federal load, Musk and his acolytes floated privatisation schemes for everything from Amtrak to the USPS—because if a rocket company can deliver packages to the moon, surely your local mailman can be replaced by something shinier and faster.

It was radical. It was ruthless. And, in classic Musk fashion, it blurred the line between visionary reform and high-stakes corporate cosplay.

Let’s take a step back…..

Naturally, not everyone is thrilled with Musk’s bureaucratic bonfire. Critics have cried foul, calling the changes too sudden, too sweeping, and, above all, too disruptive. Some have even fought back—politely, of course, with memos and committee hearings—warning that this kind of shock therapy could cause long-term damage to the very foundations of government.

And, well, they might have a point.

Because here’s the uncomfortable truth: most civil servants—even the senior ones—don’t run multiple billion-dollar empires while surviving on four hours of sleep and a diet of ambition and protein bars. Many enter public service not to change the world at warp speed, but for stability—a steady job, a pension, the elusive promise of work-life balance. It’s a system that, for decades, has worked surprisingly well. People do their time in government, then often slide into the private sector with a résumé padded by acronyms and a network of fellow paper-pushers.

It’s a quiet, dependable cycle: not thrilling, not glamorous, but functional. And for many, that’s the point.

Musk, on the other hand, doesn’t do “functional.” He does disruption, preferably at the scale of planets. So when you parachute in someone wired for warp speed into a system built for slow, deliberate plodding, you don’t get gentle reform. You get combustion.

Whether that combustion leads to renewal or ruin is, of course, still very much up for debate.

Which is precisely why appointing someone who’s never served a single day in government—and who’s made a hobby of telling critics to go fuck themselves—is, shall we say, controversial, if not outright inappropriate.

It’s not just a matter of manners, though heaven knows a touch of diplomacy wouldn’t go amiss. It’s about understanding that institutions, especially ones as colossal and convoluted as the U.S. federal government, are not rocket ships. You don’t just rip out parts and bolt on new tech, expecting everything to fly smoother. One of the first lessons any half-decent consultant learns—usually between bouts of jargon and PowerPoint—is that real efficiency comes not from bulldozing the structure, but from knowing it intimately. You study it, live it, breathe it. And then, with care and precision, you make surgical incisions—small, smart changes that trigger progress without causing a bureaucratic coronary.

Because every cog in the machine, no matter how rusty, is connected to a dozen others. Slash in the wrong place, and you don’t just cut fat—you sever tendons, arteries, entire functions. Do it right, and the system begins to hum, leaner and sharper. It achieves more. It might even generate more revenue, or at the very least, stop haemorrhaging it.

Musk’s approach, though? It’s not surgery. It’s dynamite in the filing cabinet. And while that makes for thrilling headlines and excitable shareholders, it’s not necessarily how you build a better government—it’s just how you blow one up faster.

It’s only been a few months since DOGE burst onto the scene like a Tesla with its accelerator stuck, and already, pundits are lining up on either side—some hailing it as the dawn of a lean, tech-savvy government, others whispering darkly about the slow death of institutional knowledge. But in truth, it’s far too early to pronounce judgment. Numbers can be spun, savings can be overstated, and bureaucratic wounds often take time to bleed.

And take a closer look….

What we can do, however, is examine the idea itself—strip away the circus of personalities, the Muskian mystique, the Trumpian bravado—and ask a more enduring question: should every government have its own DOGE?

The idea of something like DOGE, some disruptive force armed with tech, algorithms, and a flamethrower for red tape, appeals so strongly. Not because it’s flawless, but because what we currently endure feels not just flawed, but utterly broken.

Now, of course, everyone and their grandmother has a suggestion for how to fix it all. Ask around and you’ll get everything from “hire more staff” to “burn it all down and start over.” It’s become a sort of international pastime—complaining about government services and fantasising about how much better things would be if only you were in charge.

Politicians, naturally, love this game. They campaign on grand promises to "modernise," "streamline," and "make government work for the people." Rousing stuff. Every election season, someone emerges from obscurity with a PowerPoint and a new acronym, swearing they’ll be the one to finally fix the DMV, the VA, the post office, the lot. “Help is on the way,” they declare, while standing in front of a broken printer and a suspiciously cheerful civil servant.

Then—spoiler alert—they get elected.

And somewhere between the swearing-in ceremony and their first committee meeting, the light fades from their eyes. They discovered that the real problem wasn’t the previous government. It wasn’t even the party across the aisle. No, the problem is everyone. The politicians. The civil servants. The voters. The system. The inertia. The centuries-old machinery of government that resists change like a cat resists a bath.

And so the finger-pointing begins.

Politicians blame bureaucrats. Bureaucrats blame funding. Citizens blame both. The media throws in some outrage for good measure. Everyone is technically correct, and yet nothing changes. Because while the blame is shared, responsibility is avoided like a tax audit.

It’s a story as old as government itself: the opposition becomes the government, only to realise that the enemy isn’t the last guy—it’s the whole damn architecture—a labyrinth of committees, clearances, and outdated software held together by sticky notes and despair. And so the cycle continues, beautifully inefficient and reliably disappointing.

Meanwhile, we’re still in line at the DMV.

Despite the endless complaints, the countless jokes, and the numerous academic studies on the maddening inefficiency of government, the sad truth is that subpar public service has become not just a common experience but a global given. It’s so baked into our collective consciousness that it’s almost treated as an objective fact, as unshakable as gravity or taxes.

Whether you’re stuck in line at the DMV in Des Moines or waiting months for a permit in Port Moresby, the story is the same. Government services drag their feet with stubborn reliability. Meanwhile, across the spectrum of commerce—from the slick tech startups of Silicon Valley to corner shops in Colombo—the private sector is lionised for its speed, its innovation, its razor-sharp efficiency.

Personally, I can attest that the challenges facing public service are often exaggerated, while the private sector is far from the ideal it’s sometimes painted as. When you’re tasked with serving an entire country—millions, sometimes hundreds of millions of people—mistakes are inevitable. Compare that to a business serving a few hundred or a few thousand clients, where problems are easier to spot and fix.

The sheer scale difference between the population and the number of civil servants assigned to serve them often defies logic. Yes, some point to the Indian Civil Service under British rule—just a few hundred administrators managing an empire of millions—but those were very different times and, frankly, a fundamentally different relationship: a coloniser governing the colonised. We can’t seriously compare that to modern democratic governance, where accountability and public service are (at least theoretically) core values.

So, while public services might be flawed and frustrating, the sheer complexity and scale of their task mean that expecting near-perfect efficiency is, at best, unrealistic. Meanwhile, the private sector’s celebrated efficiency often masks a smaller scope, easier metrics, and a singular focus on profit, rather than the public good. The challenge, then, isn’t just to make government more efficient, but to reconcile its vast responsibilities with the realities of serving millions fairly and effectively.

Despite the unknowns surrounding DOGE’s actual impact on the sprawling US federal government—and despite the rather abrasive, borderline reckless style with which it has been implemented so far—I would argue that, yes, some form of DOGE in every government is a good thing. The problem isn’t the concept; it’s the execution.

So how can we do it better?

As it stands, having Elon Musk—someone who has never spent a day in government—helm this high-stakes reform effort, flanked by a cadre of private-sector loyalists, is a recipe for friction and chaos. What we need instead is something closer to a triumvirate: a leadership structure that pairs the firepower and innovation of the private sector with the institutional memory and pragmatic wisdom of retired public servants, each holding equal say in decisions.

This balance would introduce a necessary soft touch to the endeavour. The retired civil servant brings invaluable experience—an understanding of the labyrinthine workings of government and the often invisible human consequences of drastic change. Musk’s unilateral decision to slash 260,000 federal employees, with only the vague promise of AI stepping in to fill the void, would likely be tempered by someone who knows the machinery isn’t that simple. A staggered approach to workforce reduction, aligned with careful refinement of AI tools, would reduce short-term disruption and avoid long-term damage.

Moreover, better communication and public relations would help. When you’re dismantling entrenched systems, people want to understand why and how, not just face a fait accompli delivered with a shrug and a snarky tweet.

If DOGE is to succeed beyond headlines and Twitter storms, it must combine the best of both worlds—the innovation and urgency of the private sector, with the experience, patience, and institutional knowledge of the public sector. Only then can the beast of bureaucracy be nudged, rather than bulldozed, into the future.

One of the most significant problems in the public sector—the root of much of its sluggishness and, dare I say, incompetence—is its entrenched culture. The prevailing mindset, in far too many corners of government, seems to be: Get in, clock in, don’t rock the boat, and settle in for a comfortable ride—a job for life with near-zero risk of being shown the door. Pay is mediocre at best, bonuses are either token gestures or nonexistent, and the workload? Endless, with no real reward for going the extra mile.

DOGE could very well be the catalyst this culture desperately needs. By cracking down on waste and inefficiency—trimming the fat where it’s long overdue—those savings could be funneled back into meaningful incentives for the public sector. Imagine that: new, decent offices instead of crumbling government buildings; actual bonuses that make going the extra mile worth it; perhaps even a Tesla parked outside the DMV as a cheeky symbol that things are changing.

AI, of course, is already part of the equation. DOGE’s introduction of AI tools to streamline workflows and reduce pointless busywork could free up human talent for the kind of creative, impactful tasks that actually matter. If done right, this isn’t just about cutting jobs or budgets—it’s about transforming government from a slog into a service people want to be part of.

If DOGE can help governments rethink how they motivate and reward their civil servants—offering fair pay, career growth, meaningful incentives, and a work environment that actually respects and values its people—it could spark a domino effect. A happier, more engaged workforce means a smoother-running civil service, which translates directly into better, faster, more reliable public services for citizens.

It’s simple: keep the people who run the system satisfied and invested in their work, and the public benefits too. A happier shop leads to a happier public — a genuine win-win for everyone involved. If DOGE can drive that transformation, then its value goes far beyond dollars saved; it becomes a cornerstone for rebuilding trust and efficiency in government.

While all that was taking place, we returned the next day to the DMV with the appropriate paperwork and hope, only to see that the lines were getting longer because instead of two personnel manning the counter, there was only one, apparently, as the other one was out sick. We can only keep our fingers crossed and hope to make it to the counter before 5 pm and complete all this. Wish us luck!

I think some public works provide good service. We just often do not see them. Highways in Spain are rarely being "worked on," but offer great service. My last medical checkups have made me wait 10-20 min past my appointment time, but have worked really well...doc responded to digital communication within a day or so. Not stellar. But quite good. Here public is better than private for severe things, but private is quicker and sometimes more comfortable. I have both. Public covers so much and is extensive.

I do think doge like processess that seek to evaluate efficiency can be good, but DOGE is not doing what it should,.

It looks like DOGE succeeded marvellously in its actual goals, which have nothing at all to do with "efficiency".

https://snyder.substack.com/p/the-fraud-fraud

https://saltypolitics.substack.com/p/lies-and-the-lying-liars-who-tell

https://www.narativ.org/p/doge-is-the-most-comprehensive-domestic

https://navigatornews.substack.com/p/why-doge-is-an-insider-threat

https://donmoynihan.substack.com/p/skilled-technologists-are-being-forced

https://americanmanifesto.news/p/whistleblower-doge-exfiltrated-sensitive-data-and-exposed-us-systems-to-russia