BOLD, BRASH & UNAPOLOGETIC: The "Autobiography" That Trump Never Wrote

The totally unauthorized parody of the century. Hilarious, outrageous, and written exactly how he would say it—this is the greatest story never told... until now. Believe me.

Democracy is a slow process of stumbling to the right decision instead of going straight forward to the wrong one

-Anonymous

Democracy has never taken the same road twice. Though often held up as a shining universal goal — cheered on in textbooks and TED Talks — it hasn’t unfolded in any predictable or uniform way. Like all messy human inventions, democracy is more accident than design, shaped by history, habit, and no small amount of chaos.

Take Europe, for example. Democracy there didn’t just appear overnight with the wave of a noble pen. It crept in over centuries, stumbling through bloody revolutions, power struggles between kings and parliaments, and endless arguments about who gets to rule and why. It was a long, loud, often violent process — but one that allowed institutions to grow slowly, like ivy around an old building.

Now turn to Asia, where the story has often been one of speed — and shock. For many countries, democracy didn’t arrive gradually; it dropped in suddenly, often in the wake of colonial collapse, foreign occupation, or abrupt ends to dictatorship. One day, flags were being lowered; the next, ballot boxes were rolled in. In some places — India, Japan, South Korea, Taiwan — democracy managed to stick and even flourish. In others, it barely had time to unpack before being shown the door by the next strongman in line.

So why the difference? It's tempting to ask, "Why can’t Asia do democracy like Europe?" But that’s the wrong question. You can’t judge a tree by how well it mimics another forest. Instead, look at what each region started with: deep-rooted social hierarchies, colonial baggage, the aftershocks of global wars, different ways of building wealth, and very different timelines for when modern states even came into existence.

The truth is, democracy isn’t one-size-fits-all. It's not a product you can install and expect to run smoothly. It adapts — or struggles — depending on where it lands. That some Asian countries have built resilient democracies despite the odds is something close to remarkable. That others have stumbled says more about the landscape than the idea itself.

If democracy is a performance, then each region is staging its own version — using whatever props, scripts, and stagehands history happened to leave behind.

Hierarchical Traditions and the Limits of Participation

Social hierarchy—its nature, persistence, and cultural meaning—profoundly shapes the conditions under which democracy can emerge and endure.

Asia: Deference over Dissent

If democracy is the art of public disagreement, then it runs headfirst into a cultural speed bump across much of Asia: the long-standing preference for harmony over conflict, and deference over disruption.

In East Asia, for instance, Confucianism has left deep marks on the political psyche. It teaches that order springs not from votes and debates, but from moral behaviour, respect for elders, and everyone knowing — and staying in — their proper place. Challenging authority isn’t virtuous; it’s unruly.

In South Asia, the ghost of the caste system still lingers, even though it’s been outlawed. It shapes who gets heard, who gets elected, and who stays stuck. In many parts of Southeast Asia, politics runs on kinship and loyalty, not to abstract institutions but to actual families, clans, and networks of personal ties. Think political dynasties, but with stronger family dinners.

Now, none of this means democracy can’t work in Asia. It clearly has in several places. But it does mean that democracy wears a different outfit here. People often care more about whether the government gets results — jobs, order, stability — than whether it was chosen through a raucous and open vote. In many cases, legitimacy comes from performance, not process.

To put it bluntly, a well-behaved autocrat in much of Asia may be more popular than a chaotic parliament. Not because people are docile, but because the cultural script they’re working from values quiet success over noisy freedom.

Europe: Conflict as Catalyst

It’s not as if Europe came pre-installed with democracy like some constitutional starter pack, far from it. For centuries, it too was a grand pageant of hierarchies — kings by divine right, popes with armies, aristocrats in powdered wigs, and peasants who mostly died where they were born. But here’s the twist: Europe didn’t so much dismantle its hierarchies as pit them against one another.

Power in Europe was gloriously fragmented. Monarchs, the Church, feudal lords, city-states — all squabbling for control like contestants in a medieval reality show. No one authority could dominate for long, and that constant friction became a kind of accidental incubator for democratic principles.

Then came the Protestant Reformation, a spiritual insurrection disguised as theology. It not only shattered the Catholic Church’s monopoly but also gave rise to a public that could read, write, and—most dangerously—think for itself. Suddenly, obedience was optional.

Meanwhile, England (never one to be left out of historical drama) had its Magna Carta moment, when the monarchy was politely told to back off. Over time, legal systems crept in to hem in power, and parliaments—once mere talking shops for the elite—began to matter. Not overnight, but slowly, stubbornly, and with great resistance.

What emerged wasn’t just democracy, but a culture of dissent baked into the architecture of power. The push and pull between Church, Crown, and commoners left space for an increasingly assertive middle class — the merchants, lawyers, and pamphleteers — to demand rights, representation, and the right to shout back.

In Europe, democracy wasn’t gifted. It was wrestled, wrangled, and occasionally written in blood. But it stuck, mainly because conflict was built into the system. And conflict, inconvenient as it is, turns out to be democracy’s secret ingredient. Colonial Blueprints: How Empires Shaped Institutions

The British Empire: Democracy’s Accidental Midwife

Say what you will about the British Empire — and there’s plenty to say — but even as it plundered half the globe in search of tea, spices, and a good tan, it occasionally left behind some unexpectedly useful civic furniture.

Yes, the motives were colonial and unapologetically extractive. But in its wake, the Empire bequeathed what one might call “proto-democratic starter kits.” These were not gifts, mind you — more like side effects. Still, they proved oddly enduring.

For one, the common law system, with its obsession over precedent and due process, encouraged a legal culture where rules mattered more than royal whims. Courts weren’t perfect (or independent), but they weren’t entirely decorative either.

Then there were the bureaucracies — stiff, paperwork-loving civil services that ran the colonies with maddening efficiency. While their goal was to maintain control, they also instilled a habit of procedural consistency, which future governments could build upon, or at least mimic.

Elections? Well, sort of. Representative bodies were introduced in a few places to let the local elite blow off steam. These were far from democratic in the modern sense, but they did give colonial aristocrats a crash course in ballot-counting and public pandering.

Crucially, the British exported their language, not just English as grammar but English as a gateway to Locke, Mill, and parliamentary democracy. Through mission schools and universities, a generation of post-colonial leaders learned to argue, legislate, and protest, often using the very tools of the Empire to dismantle it.

But let’s not break out the bunting. For every judicial structure or school, the British also left behind something far less noble: entrenched inequalities, ethnoreligious fault lines, and a political culture shaped more by divide-and-rule than by civic unity. In India, Malaysia, and across Africa, the legacy was a double-edged sword: democratic potential tied up in knots of colonial mischief.

If the Empire gave democracy a skeleton in some places, it also ensured that the flesh around it would be fragile, contested, and often scarred.

The French and Dutch: Civilisation, Extraction, and the Art of Leaving a Mess

If the British Empire left behind a battered toolkit of democracy, the French came bearing a sledgehammer — and a mirror. Their colonial approach wasn’t merely about rule; it was about transformation. The mission? To turn colonised subjects into Frenchmen in spirit, if not quite in citizenship. It was an empire as theatre, complete with liberty, equality, and fraternity — for some.

Under French colonialism, local governance wasn’t decentralised or participatory; it was centralised, Parisian, and often oblivious. The colonies were run from the top down, with the bureaucratic flair of the French state and the cultural superiority of the Enlightenment, minus the actual Enlightenment. Assimilation was the doctrine, but it often produced a thin crust of French-educated elites perched uneasily atop vast rural populations who neither spoke the language nor recognised the laws that governed them.

Direct rule dismantled traditional authority structures but didn’t bother replacing them with anything meaningfully inclusive. The result? Power vacuums, fragile institutions, and societies torn between imported republican ideals and local political realities.

When independence came, it came suddenly — not with a baton-passing ceremony, but more like the abrupt slamming of a door. There was little time for democratic training wheels. Many former colonies found themselves tossed the keys to a state they had never really been allowed to drive.

As for the Dutch in Indonesia, their colonial legacy was far less theatrical but no less damaging. The Dutch were not interested in assimilation but in nutmeg, rubber, and shipping lanes. They governed with minimal pretence and maximal efficiency, turning Java into a plantation and the rest of the archipelago into a revenue stream. Indigenous empowerment was not on the menu. Where they existed, institutions were extractive by design and hollow at their core.

In both cases — whether dressed up in tricolour or cloaked in Calvinist pragmatism — the colonial legacy left little in the way of democratic scaffolding. A brittle political inheritance remained: centralised, disconnected, and remarkably ill-prepared for self-governance.

The Philippines: Ballots, Haciendas, and the American Way

In the Philippines, the United States arrived with a Constitution in one hand and a bayonet in the other. Eager to export democracy—along with tariffs and military bases—American administrators introduced the full pageantry of representative government: elections, a legislature, a functioning judiciary, even a bill of rights. It was democracy, at least in form.

But behind the trappings of Jeffersonian virtue stood a reality far older and more familiar: rule by the landed gentry. The same oligarchic families who had dominated under Spanish colonialism were left firmly in place, merely swapping one imperial landlord for another. Washington taught the Filipinos how to vote, but not necessarily how to govern—unless governing meant protecting sugar barons and hacienda owners from the inconveniences of social reform.

The result was a democratic façade with a feudal foundation—a system that could hold an election with impressive punctuality but failed, year after year, to touch the deep roots of inequality that strangled genuine political participation. It was liberty dressed in costume: formal institutions performed the part of democracy while leaving the real levers of power untouched.

This was the American legacy—noble intentions and speeches, all in service of a social order that remained stubbornly unequal, and, in many cases, deliberately so.

Europe’s Advantage: Institutional Autonomy

European nations developed democratic systems organically, without the disruption of colonial rule. Colonial expansion even bolstered Europe’s middle classes and financed democratic reform at home, while undermining similar developments in colonised societies. This asymmetry had lasting consequences.

War and Revolution: Disruption, Transformation, and Divergence

Global conflicts were pivotal in shaping political trajectories, often accelerating democratic or authoritarian outcomes.

Europe: From the Ashes, a Ballot Box

If ever catastrophe had a silver lining, it was Europe in the aftermath of its own suicidal spasms—the First and Second World Wars. The Great War, having slaughtered a generation and toppled thrones from Vienna to Istanbul, left behind a landscape littered with graves and the intoxicating promise of national self-determination. It was a promise that would be exploited and betrayed in equal measure, but it felt like history’s moral correction for the moment.

Then came World War II, a conflict so total and so morally obscene that it obliterated any residual romance with fascist strongmen and their jackbooted visions. By the end of it, liberal democracy—once the embattled idea of pamphleteers and parliaments—suddenly seemed not only desirable but necessary. The Americans, fresh from playing arsenal to the Allies and moral compass to the postwar world, swept in with the Marshall Plan and NATO, rebuilding Western Europe with money and ideological purpose.

Democracy in Western Europe wasn’t merely restored—it was fortified, institutionalised, and draped in stars and stripes. The result was a continent that, despite centuries of monarchs, wars, and inquisitions, began to resemble what it had once colonised: a federation of liberal democracies.

Even Eastern Europe, long under the dead hand of Soviet autocracy, managed a spirited if uneven democratic awakening after 1989. But unlike their Asian counterparts, many of these states could call upon deep traditions—civic institutions, national memory, resistance movements—when cobbling together new democratic orders. Their democracies, while fragile, did not appear to fall from the sky, but instead rose from a dormant historical soil, long tilled by centuries of pluralist strife.

Asia: Revolutions, Not Resolutions

If Europe's brush with apocalypse birthed ballots and bureaucrats, Asia's encounter with the 20th century’s great upheavals tended to elevate bayonets and bureaucrats in fatigue jackets. Where Europe staggered toward democracy after total war, Asia more often stumbled into revolution, partition, or paternalist command.

Japan, famously, didn’t so much embrace democracy as have it stapled onto its imperial carcass by Douglas MacArthur and a team of American constitutionalists. The result—a pacifist state with democratic trimmings and a lingering reverence for hierarchy—was more a geopolitical project than a grassroots movement. Still, it held.

China, by contrast, leapt headlong into ideological purgatory. The end of World War II offered no democratic dawn but rather a vicious civil war, culminating in a red flag hoisted over Tiananmen. Mao’s revolution was many things—utopian, brutal, tragically theatrical—but it was never interested in pluralism or the ballot box. Democracy wasn’t delayed in China; it was exiled.

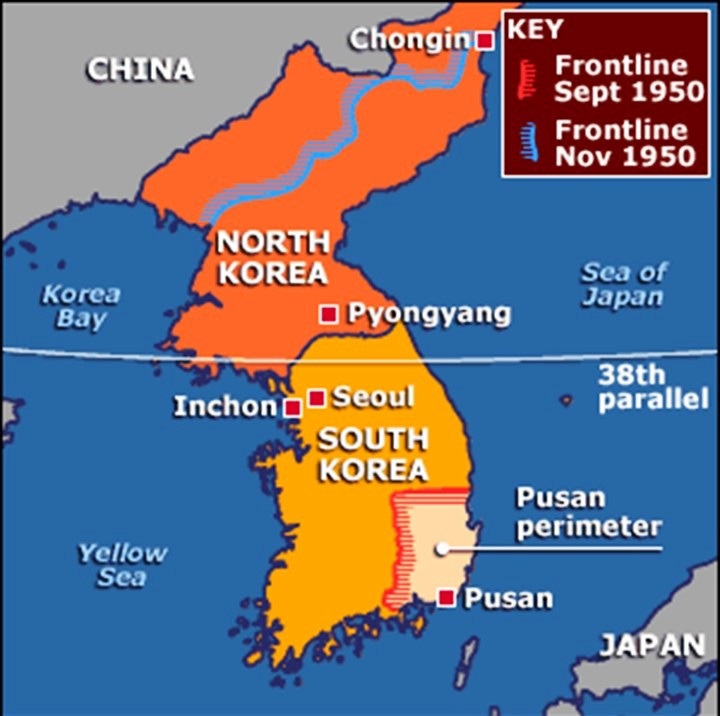

Korea, that unfortunate peninsula, was sliced like a political wishbone by Cold War cooks. In the South, a U.S.-backed regime flirted with democracy before diving into decades of dictatorship, while the North embraced dynastic totalitarianism so hermetically sealed it makes Orwell seem optimistic.

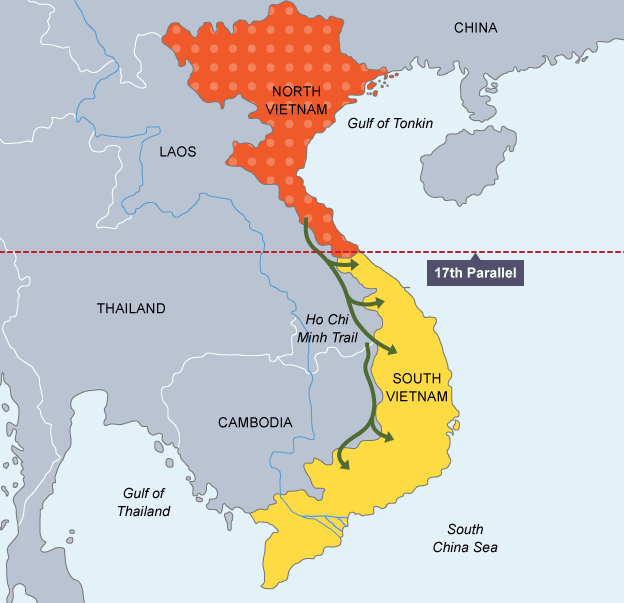

Vietnam told yet another tale—one of heroic resistance that curdled into one-party rule. What began as a battle against colonial overlords turned into a war machine whose revolutionary legitimacy excused the absence of civic freedom for decades.

Then there’s the Indian subcontinent: decolonised with bureaucratic pomp and violent haste, the region gave us two of the most instructive counterpoints in democratic development. India, defying the odds, built a sprawling, cacophonous democracy from the bones of empire, while Pakistan has wobbled between generals and judges, caught in a Hamlet-like indecision about who should actually run the show.

In short, while Europe's wars decapitated kings and fascists, often opening space for democracy to grow, Asia’s conflicts tended to consolidate power, tighten control, and usher in states defined less by deliberation than by discipline. Where Europe found itself reborn through pluralism, Asia often embraced order, sometimes with guns and slogans, but rarely with a free vote.

Growth Without Liberty: Asia’s Authoritarian Paradox

If democracy were truly the natural offspring of prosperity, Asia would be the mother of all republics. Instead, the region gave us a paradox: gleaming skyscrapers rising above tightly managed political systems, GDPs that soared even as civil liberties stagnated. In many ways, it was capitalism without the troublesome baggage of consent.

The so-called developmental state—that technocratic deity invoked from Seoul to Singapore—was less a cradle of democracy than a temple of order. In South Korea and Taiwan, economic miracles were conceived in the boardrooms of central planners and delivered by generals in mirrored sunglasses. Only once growth was assured and the working classes emboldened did the democratic thaw begin.

Elsewhere, the story followed a different arc. Singapore, that glimmering autocracy in miniature, offered citizens the ultimate Faustian pact: wealth in exchange for docility. Its counterpart, Malaysia, married electoral formalities with elite entrenchment, where political change was allowed, as long as it didn’t involve the ruling coalition losing too much sleep.

And then there’s China, the grand exception that now threatens to become the rule. With economic expansion that turned peasants into consumers and ghost towns into global markets, Beijing achieved the dream of many a Western CEO: a compliant workforce, no unions, and no pesky opposition parties. The Communist Party became a master of political origami, folding Marxist rhetoric into market pragmatism while insisting that freedom of choice at the mall was a fine substitute for freedom of speech at the ballot box.

Modernisation theory, that quaint academic relic, had confidently promised that middle-class affluence would lead to liberal awakening. But in much of Asia, the bourgeoisie found order rather comforting. Better a competent autocrat than a messy parliament. And so, rather than storming the barricades, many chose to invest in condos, not constitutions.

This isn't to say democracy is unwelcome in Asia. But in the contest between ballots and balance sheets, it’s clear which one won the opening rounds.

State Formation and the Timing Trap

One of the most underappreciated factors in democratic development is the sequence of nation-building and state formation relative to democratisation.

The Privilege of Precondition: Europe’s Head Start on Democracy

It’s far easier to hold elections in a house that already has walls. European democracies, for all their imperfections, had the advantage of arriving late to their own party—after the furniture had been arranged, the family squabbles settled, and the locks installed on the doors.

Before ballots were cast, Europe’s states had done the heavy lifting of nation-making. Shared languages, forged often through war and church, and common mythologies—equal parts heroic and fabricated—bound people together in ways that made the idea of a single sovereign demos at least vaguely plausible. No small feat, considering that for centuries, your average European peasant was more loyal to the village priest than to any abstract “nation.”

Borders, too, had mostly stopped moving—at least until the 20th century tore them up again. But even then, the foundational work had been done: institutions had matured, laws had calcified, bureaucracies had become irritatingly efficient. The result? When democracy finally arrived, it wasn’t tasked with building the state. It was simply asked to run it.

This mattered enormously. Political contestation could unfold within the safe confines of legitimacy—conflict, yes, but mostly with rules. Democracy did not arrive as a saviour or a wrecking ball; it came dressed in the robes of continuity.

Contrast this with parts of Asia and Africa, where the state itself was often a recent, brittle invention—lines drawn in sand by departing colonisers or unified at gunpoint by postcolonial strongmen. In such places, democracy had to do far more than mediate disagreement; it had to manufacture the very thing being disagreed over: a shared sense of who "we" are.

Europe may not have invented democracy, then, but it certainly benefited from having built the stage before the curtain rose.

Building the Plane While Flying It: Asia’s Triple Burden

Where Europe got to construct its democratic institutions after the scaffolding of the nation-state was firmly in place, most Asian countries were handed a very different challenge: build the house, lay the plumbing, and host a dinner party—all at once.

Colonialism, which is the most benevolent of historical accidents (as some still insist on framing it), left behind borders drawn with all the precision of a blindfolded cartographer. Mountains, rivers, tribes, tongues—none of these trifles were allowed to get in the way of clean lines on a map. When independence arrived, it often did so with borrowed constitutions and borrowed problems.

Nation-building, then, became not a celebration of unity, but a scramble for identity. Independence movements, which had demanded unity against the coloniser, quickly fractured once the unifying enemy vanished. Civil war replaced colonialism faster than the new flag could be raised in some places.

The state itself—barely more than an exoskeleton left behind by retreating colonial powers—had to be made real. That meant roads, schools, taxes, and armies. And above all: authority. In such contexts, democracy was often seen not as a luxury but as a liability. You don't open the floor to debate while the floorboards are still being nailed down.

So, strongmen emerged. Not all were villains, and not all democracies vanished. But in many cases, centralised power became synonymous with survival. And when you’re building a state from scratch, survival tends to win the argument.

Revolutions are Loud, but Constitutions are Quiet

There’s an old revolutionary adage—misattributed like most good ones—that says power flows from the barrel of a gun. Quite. But as it turns out, so too does bureaucracy, censorship, and a conspicuous shortage of press freedom.

Countries that won independence through revolution—Vietnam, Indonesia, and their ideological kin—often emerged not with deliberative assemblies but with command structures. Wartime mobilisation is rarely democratic, and it tends to stick. The habits formed in jungle warfare or guerrilla cells—centralised decision-making, suspicion of dissent, charismatic strongmen—don’t lend themselves easily to parliamentary procedure. When the enemy retreats, the war cabinet renames itself the government.

By contrast, those countries that negotiated their independence—India, Malaysia, Ghana, to name a few—tended to inherit a functioning, if flawed, administrative apparatus. Courts, civil services, and an electoral framework were left behind like an old colonial overcoat: awkwardly tailored, but warm enough in a storm. The transition was often smoother, though by no means idyllic.

India remains the shining, maddening, miraculous exception. A subcontinent masquerading as a republic, it stitched together languages, religions, castes, and ideologies under a democratic umbrella many thought would collapse under its own weight. That it didn’t—and still hasn’t—is due in large part to the inclusive, if sprawling, independence movement led by the Congress Party. Whatever else it became later, at the founding hour, it was a coalition of the many, not a vanguard of the few. And that made all the difference.

Asia’s Democratic Spectrum: Regional Variations

Rather than a monolith, Asia contains diverse democratic trajectories shaped by local contexts.

South Asia: One Subcontinent, Many Fates

If democracy were a game of numbers, India would have won long ago. With over a billion citizens and an electoral apparatus that regularly mobilises more voters than the population of Europe combined, it remains—however battered—the world’s largest democracy. That it has endured is no small feat, aided by a federal structure that allows for local peculiarities, a judiciary that occasionally remembers its spine, and founding leaders who, whatever their flaws, believed deeply in pluralism over purges.

Next door, Pakistan took a rather different route—less ballot box, more barracks. The military, perpetually in a state of ‘reluctant’ intervention, developed a habit of stepping in when civilian politics became too noisy or too democratic for its liking. Power in Pakistan has long resided not in parliament but in cantonments.

Born in blood and partitioned ideals, Bangladesh has wavered between electoral enthusiasm and authoritarian relapse. While resilient in spirit, its democratic institutions have often been treated like light switches—flipped on and off depending on who’s in charge.

These divergent paths underscore this: geography and culture may be shared, but political destiny is not. The institutions you inherit, the conflicts you endure, and the leaders you elevate all conspire, quietly or catastrophically, to shape whether democracy blooms or buckles.

East Asia: Divergence Beneath the Surface

Japan, famously the only nation to have been nuked into modernity, emerged from its imperial past into a remarkably stable democracy—albeit one midwifed by American occupation and underwritten by a pacifist constitution that still raises eyebrows at home and abroad. Yet even before the war, Japan had flirted with parliamentary institutions, however fleetingly. Post-war reconstruction gave those democratic embers room to glow.

South Korea and Taiwan, by contrast, took the more familiar path of "prosperity first, freedom later." Both endured decades of stern authoritarianism while their economies roared to life—proof that steel mills and ballot boxes don’t always arrive in tandem. Only in the 1980s did democracy emerge from the shadows, not through revolution, but through hard-won protests, strategic concessions, and the rising political clout of a middle class tired of being managed.

And then there's China—the ever-present outlier and proud of it. Here, the Party remains the state, the state remains the Party, and democracy is considered a Western conceit best kept outside the firewall. "Socialist governance with Chinese characteristics" is the official euphemism, though what those characteristics are, beyond surveillance and party supremacy, remains debatable. With economic success serving as both justification and distraction, liberal democracy is not just absent but ideologically unwelcome.

Thus, we find the full spectrum within one region—from constitutional monarchies to maturing democracies to iron-fisted technocracies. Geography binds them; political destiny does not.

Southeast Asia: Democracy by Fits and Starts

After enduring the long shadow of Suharto’s New Order—a regime where stability often came at the barrel of a gun—Indonesia managed a democratic turn in 1998 that surprised even its most ardent skeptics. Since then, it has become an improbable standard-bearer for pluralism in the region, proving that archipelagos can cohere both geographically and politically.

Singapore, meanwhile, stands as a curious case of electoral choreography. There are elections, yes—held with metronomic precision—but genuine political competition is kept on a tight leash. The People's Action Party has mastered the art of rule by performance: efficient, technocratic, and ideologically Teflon-coated. Dissent exists, but in a muted tone, you’d need a stethoscope to detect it.

The Philippines is democracy’s tropical rollercoaster—lurching between idealism and demagoguery. It boasts a free press, lively elections, and constitutional guarantees, yet remains ensnared in a culture of elite dominance and dynastic populism. Marcoses fall, and Marcoses rise again. The ballot box is active, but so is historical amnesia.

Thailand completes the quartet with a revolving door between civilian rule and military coups. A constitution here is often just the prelude to its subsequent suspension. Behind its smiling tourism posters lies a state forever caught in a tug-of-war between monarchist nationalism, military paternalism, and a citizenry still demanding its democratic due.

Together, these nations underscore a regional truth: democracy may exist in theory, but in practice, it is endlessly adapted, interrupted, and reinterpreted. One might say it's less a form of government here than a work in progress—subject to review, override, and the occasional coup.

Beyond Institutions: Not Just the Ballot, but the Backdrop

To treat democracy as nothing more than an electoral mechanism is to mistake the performance for the play. Democracy is, at its core, a cultural contract—a negotiated relationship between power and the people, framed not only by laws but by deeply held beliefs about authority, obligation, and the self.

In much of Asia, authority is not viewed as a necessary evil to be contained, but as a moral force to be respected. Leadership is expected to guide, not just to govern. Confrontation, the cherished lifeblood of Western liberalism, is often viewed as socially corrosive—less a democratic right than a failure of etiquette.

And rights? They may come wrapped not in the parchment of individualism, but in the fabric of community. What matters is not the solitary voice shouting “freedom!” but the collective harmony that keeps the house standing.

This is not, as some would have it, a betrayal of democracy. It is a variation on the theme. Democracy must always speak in the vernacular. Where Western models are fond of noisy dissent and gladiatorial debate, many Asian models favour quiet legitimacy and negotiated consensus. The essence is not lost—it simply wears different clothes.

What’s required, then, is not the mechanical transplantation of Westminster or Washington into foreign soil, but a recognition that democracy—if it is to flourish—must root itself in local idioms, local histories, and local ideas of justice. Anything else is not democracy, but mimicry.

Evolution vs. Imposition: The Tempo of Democracy

Perhaps the most fundamental contrast lies in how democracy emerged in Europe and Asia.

The Gradual Evolution of European Democracy: Revolution or Evolution?

In Europe, democracy did not arrive in a flash of enlightenment, nor was it handed down from a benevolent monarch. No, it took centuries to unfold—gradually, painfully, and often violently—through a process more akin to erosion than a sudden breakthrough.

It began with the slow, inexorable cracking of absolutism, that once-immovable fortress of royal power. The monarchs, draped in divine right, were eventually dethroned—not by a single blow, but through the steady erosion of their authority by nascent bourgeois and working-class demands. Ordinary people, for centuries deemed nothing more than the furniture of the state, began to stand up and say, "No, not this time."

Meanwhile, intellectual ferment stirred the pot, as ideas about individual rights and personal freedoms began to seep into the common consciousness, like water through stone. These ideas weren't born in the velvet salons of the aristocracy, but in the coffeehouses and pamphlets of the discontented. They became the foundation for what we now call "democracy."

Of course, all this progress was hardly linear. Europe's democracy didn’t evolve like some idyllic pastoral scene. It was messy, uneven, and full of false starts. Revolutions erupted, like those in 1789 and 1848, shaking the political landscape like a dog trying to rid itself of fleas. But those revolutions, for all their blood and fire, didn’t erase the progress that had already been made. They built upon it, adding layers of experience, of collective memory, and of ideas that had already started to take root.

Even when communism collapsed in 1989, it was not an abrupt rejection of all that came before; it was the culmination of decades of disillusionment, reform, and the unwillingness of old structures to adapt. The people may have been chanting "Freedom!" but they were echoing centuries of struggle.

Asia: Democracy by Compressed Timelines

In Asia, democracy did not unfold like a slow, deliberate dance, but rather burst onto the stage, often as an afterthought or imposition.

For many Asian countries, democracy was something handed down from on high, imposed at the moment of independence or during some foreign occupation. In Japan, it came courtesy of American occupation, as the victorious allies carved out a new order from the ashes of war. In other parts of the continent, the Cold War pressed governments into adopting democratic forms as a price for foreign aid, an awkward coupling of political form and strategic necessity. Democracy was often less a genuine expression of the will of the people, and more a concession to geopolitical forces.

But here’s the rub: democracy in many parts of Asia was often institutionalised, without the necessary social transformation that would have given it real substance. While elections were held, parliaments formed, and constitutions signed, they were merely the skeletons of democratic ideals. The marrow—the civic norms, the understanding of rights, the delicate balance between authority and individual freedom—was often missing. Without this slow and organic development, many systems remained democratic only in name, while in practice they were fragile, susceptible to the winds of authoritarianism or military coups.

In the absence of a genuine democratic culture, the mechanisms of democracy—however polished—could not truly take root. Instead, you had a facade of democracy, propped up by international legitimacy but ultimately hollow, unable to withstand the pressures of power and patronage.

Conclusion: Democracy Without a Template

The uneven progress of democracy in Asia is not some damning indictment of cultural inadequacy or civilizational inferiority. No, it is instead a vivid reminder that history, unlike propaganda, resists simplification.

When we compare Asia with Europe, the question is not "who wore democracy best?"—as though this were a political fashion show—but rather: How does democracy change its costume, its voice, and its very anatomy when it is dropped into vastly different theatres of history?

Europe's democratic drama was a slow-burning epic, with centuries of blood, fire, and bargaining. Asia’s encounter with democracy has more often resembled a crash course—interrupted by colonialism, carved up by Cold War strategists, and crash-landed into newly independent states still nursing the wounds of empire.

And yet—look again. With its dizzying plurality, India stubbornly insists on holding elections larger and louder than any in the world. Once ruled by iron fists, South Korea and Taiwan now boast vigorous democracies born of sweat, struggle, and student protests. These aren’t flukes. They’re evidence that while structural barriers may slow democracy’s march, they cannot always hold it back.

The moral? Asia doesn’t need to cosplay the European script, reciting lines from Montesquieu and Locke while dressed in borrowed robes. Its political future, if it is to be democratic, will not come from mimicry, but from invention. Indigenous democratic ideas, forged in local fires, tempered by unique histories—that is where the future lies.

Democracy, like any good idea, travels. But it only survives if it learns the language of the land.

Democracy’s Uncertain Future: Asia and the Global Order

As Asia confidently steps onto the geopolitical stage—not as a pupil of the West but as a co-author of the global script—it brings with it not only economic heft and strategic nerve but also a vexing, fascinating question: What shape will democracy take in a world no longer bound to a Western blueprint?

Enter China, stage left, with its model of authoritarian capitalism—a gleaming technocratic leviathan that gets things done without the inconvenience of public dissent. To many in the Global South, weary of chaos in the name of liberty, the Chinese experiment doesn’t look like an aberration. It looks like a viable path, especially when many liberal democracies, once smug exporters of their systems, are now busy discrediting them at home.

Which forces us to confront several uncomfortable questions:

Will the glow of democratic legitimacy outlast its current power outages?

Can a regime draped in electoral theatre and ruled by a strongman still call itself a democracy with a straight face?

And in a world where “good governance” increasingly means potholes fixed and Wi-Fi delivered, will messy public deliberation still be seen as a virtue—or a bug?

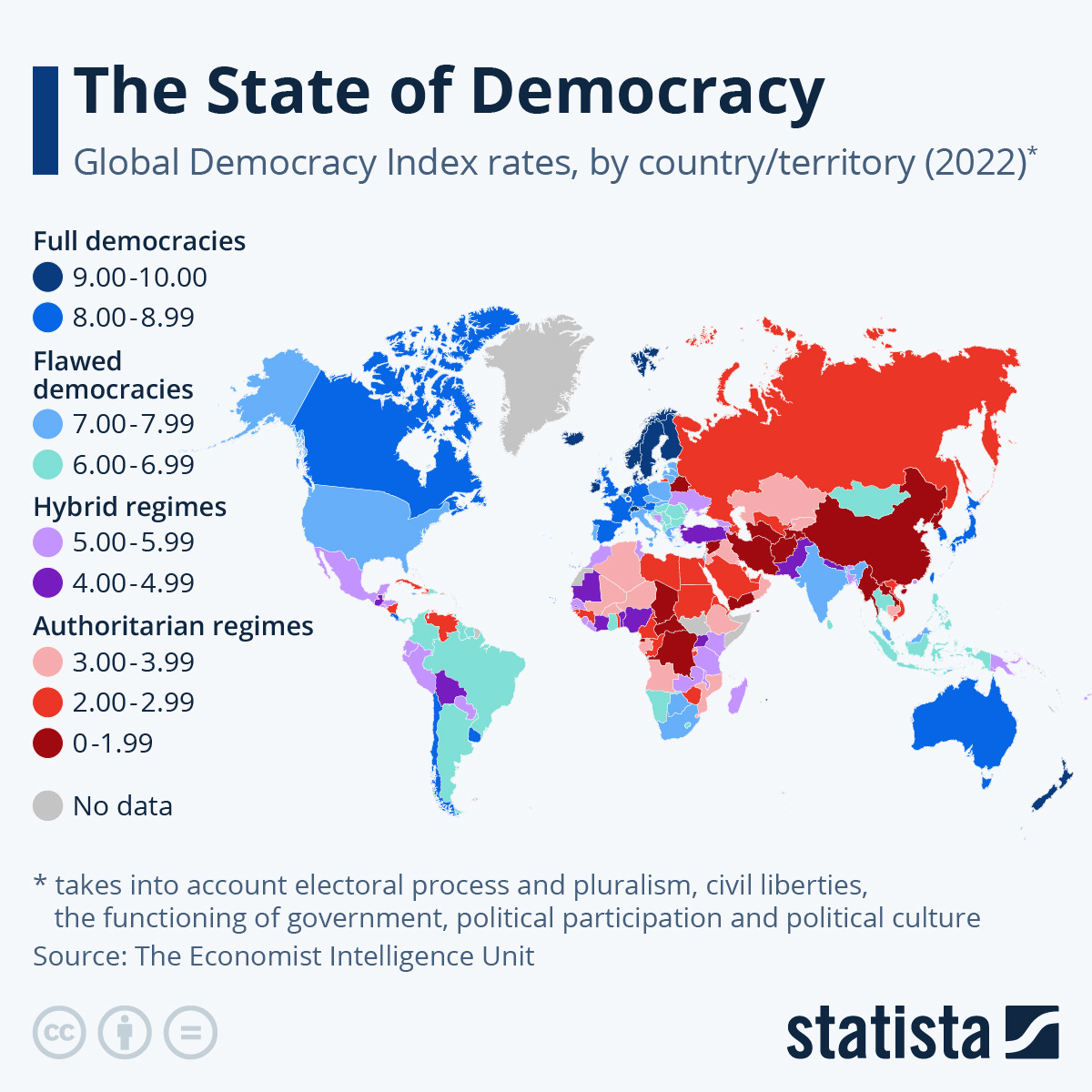

The reality is that the 21st century is unlikely to crown a single political victor. Instead, we are entering an era of ideological polyphony, where liberal democracies, hybrid regimes, and digitally augmented autocracies all jostle for space, influence, and narrative dominance.

Democracy in Asia, then, is not a final product. It is a work in progress, a palimpsest of ideals and improvisations. Its success—or failure—will hinge not on mimicking European precedent but on the ability to translate timeless democratic principles into local idioms and institutions that command both legitimacy and loyalty.

That effort lies the real challenge—and the real hope—for those who believe that human dignity should not depend on the generosity of power but on the power of participation.

☕ Love this content? Fuel our writing!

Buy us a coffee and join our caffeinated circle of supporters. Every bean counts!

Post-Rhetoric: The US and Democracy Promotion in the Middle East and North Africa

In the early 2000s, democracy became a buzzword, especially in the context of the US push to introduce it to the Middle East. The idea was that being part of the democracy club meant stability, prosperity, and a clear development path. This notion gained strength because many of the most stable and developed nations were democracies, echoing Churchill's…

Trump, Re-elected: the Russian Perspective

Many words have been said, many lines written, and many opinions raised about Donald Trump, as well as about his presidency – both his first one and his potential second one – and his complex relationship with Russia. For decades, if not centuries, Russia has viewed the West in general (especially the UK, with deep historical reasons for that) and the U…

![Photos: A Glimpse of Afghanistan Before and During a Historic Election [UPDATED] | Asia Society Photos: A Glimpse of Afghanistan Before and During a Historic Election [UPDATED] | Asia Society](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!4Uc2!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fe36d023a-3bee-4bd3-99e5-6f6293d7539c_600x394.jpeg)

Excellent post that roots democratic and non-democratic government development in history. I like the ambition--amd find the rooting of current government in history and happenstance cogent. This, should theoretically, help intervene in the cases where one wnats to see democracy flourish, and detect possible dangers.

It is cetainly strange to see the attack on its very self that has existed in the west for the past few decades. The current political situation also, as you point out, makes the Chinese model seem like an alluring path forward. However, the extent to which this path is a desirable one, is worth pondering and exploring... otherwise it may be too late (or is that a good thing?)-