Are We Living in a Black Mirror Episode?

How Technology, Once a Tool for Progress, Is Now Fueling Our Downfall — As Foretold by Black Mirror

The new season of Black Mirror has landed on Netflix, and I watched the whole thing in a single, gluttonous weekend. I first stumbled across Black Mirror years ago, with that infamous first episode — unforgettable, though somewhat in the way one remembers a bad accident. It was clever, unsettling television, the sort that stayed with you long after the credits rolled.

Then came the inevitable decline. Once Netflix got its hands on it, the show grew slicker but somehow lost its edge, like a blade polished to uselessness. For a while, I thought it was finished.

But, to my surprise, this latest season shows signs of life. It’s not brilliant, but it’s not bad either. It feels almost like the Black Mirror of old — though, of course, that's only my opinion, and you're welcome to disagree (at your own risk)..

The "Autobiography" Trump Should Have Written

The unauthorized parody that's taking the world by storm!

Ever wondered what goes on inside that famous head of hair? Now you can find out in this hilarious, no-holds-barred imagining of the memoir he'd write himself—if he had the time between "making deals" and "being the best."

Written with all the subtlety of a gold-plated escalator and the modesty of a 70-story tower with his name emblazoned on it, this parody captures the voice, the vocabulary, and the... very, very large opinions that made him famous.

WARNING: May contain the greatest words, the most beautiful sentences, and definitely the biggest claims you've ever read. Tremendous stuff. The most tremendous. Everyone's saying it.

For the uninitiated, Black Mirror is a television series that employs dark, inventive fiction to hold a cracked mirror up to our so-called technological "progress." Each episode is a self-contained cautionary tale, reminding us — sometimes with grim humour, sometimes with brutal clarity — that every shiny new gadget carries the seeds of its own disaster.

At the helm is Charlie Brooker, a man whose imagination one can only describe as disturbingly fertile. One watches his work and wonders: Is he simply inventing these scenarios, or quietly taking notes on the future? Time and again, an episode airs, and within a few years — sometimes months — life, with all its dreary inevitability, obliges by imitating it. This eerie, almost clairvoyant quality lends Black Mirror its unsettling power; it doesn't merely depict dystopias — it charts them.

Formally speaking, technology refers to the application of scientific knowledge for practical purposes, particularly in industry. That’s the textbook definition — sterile, precise, and about as thrilling as a VAT receipt. In everyday terms, however, "technology" has come to mean anything that glows, beeps, whirrs, or flashes — preferably while promising to make life simpler, faster, and less bothersome. A smartphone, by this reckoning, is a technological marvel; a screwdriver, though undeniably a product of human ingenuity, is dismissed as quaint, largely because it doesn’t chirp, buzz, or fit snugly into a pocket.

Such is our fetish for the shiny and the sleek that we instinctively assume all technology is a net good — a triumphant march towards convenience and enlightenment. And should any modern Cassandra dare suggest otherwise — that perhaps not every new gizmo is a gift from Olympus — they are swiftly branded a Luddite, a crank, or worse, a bore.

Popular culture has hardly helped matters. In fiction, technology is invariably portrayed as the hero’s ally, often riding in at the eleventh hour like a deus ex machina in digital form. Whether it’s a lightsaber (a personal favourite) or Cerebro from X-Men, the message is clear: in the right hands, tech saves the day, restores order, and looks marvellous while doing it. How wonderfully naïve.

Which is precisely why Black Mirror seized my attention and refused to let go. Where most of popular culture seems content to slobber over every new shiny gadget — peddling utopian visions of endless convenience — Black Mirror does something infinitely more interesting: it shows us how these marvels might well ruin us, and in ways we scarcely have the imagination to fear. The show doesn't merely cast a sceptical eye over our inventions; it gleefully rips apart the myth that technology is our benevolent saviour. I was, and remain, utterly hooked.

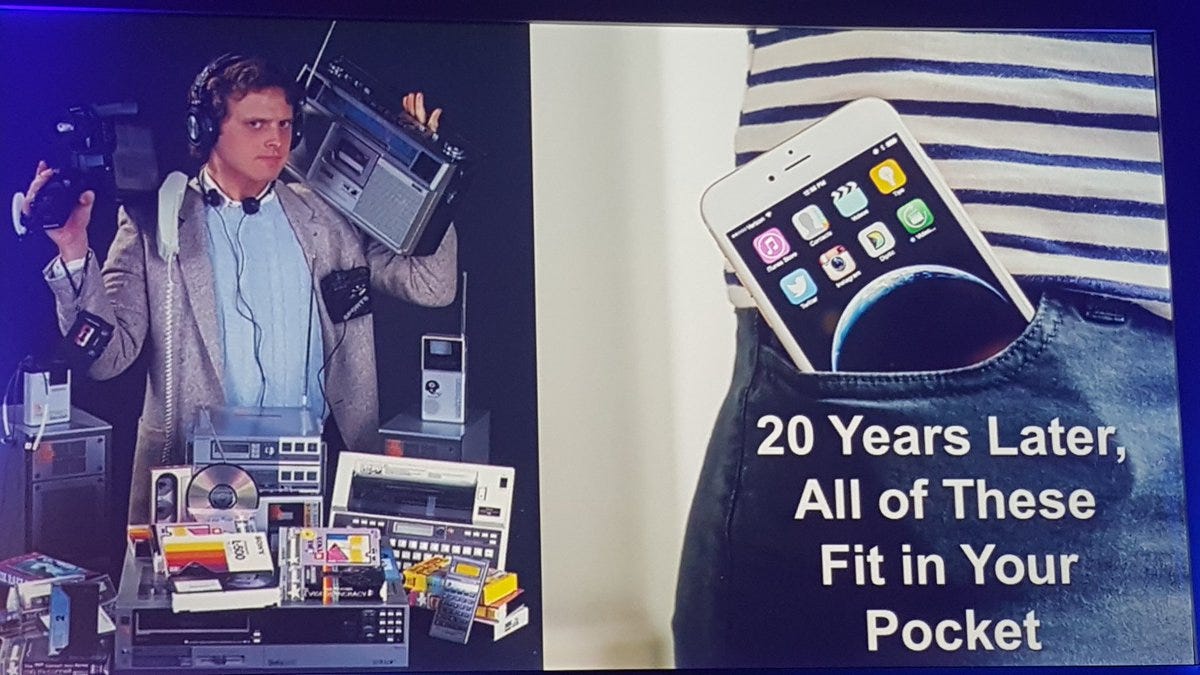

Though it makes for riveting television precisely because it explores what others daren’t, I sometimes wonder: does Black Mirror truly offer a warning, or is it simply keeping a diary of the inevitable? I am, after all, a child of the early tech age — not quite born with a smartphone welded to my hand, but close enough to have witnessed the slow compression of an entire roomful of gadgets into a device that now fits neatly into a back pocket.

I watched us move from the clunky novelty of email, to the ephemeral chatter of AOL Messenger, to the frozen grimaces of Skype calls, and finally to the all-consuming leviathan of social media, where even international conversations are free, instant, and usually witless. Where once I thumbed through dusty library books, proudly memorising reams of more-or-less useless information, now I thumb through my phone, with entire libraries and lecture halls available at the merest swipe.

And as for childhood dreams: the Tesla, that sleek, humming symbol of the future, edges us ever closer to the Knight Rider fantasies of the early ’90s. As an eight-year-old, the idea would have seemed laughable. Today, it’s simply Tuesday.

These advancements, it must be said, have made my life incomparably easier. What once took weeks — trawling through library stacks and composing tedious reports in high school — shrank to mere days by the time I reached graduate school. I now dictate my daily tasks to my phone, whereas once I carried around a battered little notebook and an equally battered little pen, jotting down to-do lists like a medieval scribe.

Once upon a time, passing a driving test meant mastering the arcane arts of reverse and parallel parking. Now, with the right vehicle, I could fall asleep at the wheel in New York and wake up in Philadelphia — not that I’m recommending it. Air travel has undergone a similar transformation: I once lugged paperbacks across continents like a literary Sherpa; today, a slim Kindle, loaded with a thousand books I’ll never finish, does the job nicely.

Even my workouts — formerly charted in sweat-stained journals with wildly exaggerated claims of progress — are now monitored with clinical precision by a small watch that buzzes, nags, and congratulates me in equal measure. Thanks to these technological marvels, I am, in many ways, a more efficient, capable, and well-rounded creature than I would otherwise have been.

However much I might try to resist, it’s become increasingly difficult to ignore the corrosive effects these technological augmentations have had on me. The change is subtle at first, a gnawing sensation that doesn’t make itself known until it’s already done its damage. Once, I had a mind capable of effortlessly recalling random facts and trivial details, a sort of mental filing cabinet that only required a flick of the wrist to access. Now? I can barely remember a phone number or the name of that book I read just last week. The promise of limitless knowledge has turned out to be more of a curse than a blessing, as my ability to retain anything outside of my phone’s cloud storage has steadily diminished.

The instant gratification that technology provides — whether it's a rapid download, a tap-to-pay transaction, or a swipe of a screen — has turned me into a petulant, impatient creature. I can’t wait for the minor, natural delays of life without feeling the faint stirrings of frustration, as if the slow, unreliable machinery of human existence is personally betraying me. And with that impatience, the empathy I once thought was a given has quietly eroded, leaving behind only the brittle remnants of human connection.

Then there’s the soul-sucking phenomenon of doom-scrolling: one minute I’m idly checking the news, the next I’m lost in a vortex of vapid cat videos and mind-numbing reels. An hour has slipped away, never to return, and for what? Nothing but a sharp decline in productivity and a duller sense of purpose.

And it’s not just me. I remember being in Geneva, of all places — a city where diplomacy, conversation, and authentic human interaction are supposed to be the order of the day. There, in the hotel lobby, were twenty people, all hunched over their phones, staring at screens with the rapt attention of addicts. Some were in groups, yet no one was talking to each other. It felt like a scene from Black Mirror, only it wasn’t fiction. It was real life, and it was horrifyingly normal.

What’s more, I’ve grown disturbingly comfortable with the convenience of digital communication. I’ve even found myself preferring it to the messier, unpredictable reality of face-to-face interaction. Worse still, I’ve embraced a practice I would have once found utterly contemptible: “ghosting.” With a few taps, I can vanish from someone’s life without a trace of guilt, without the need for an explanation. Technology hasn’t just made this possible; it’s made it all too easy, even for someone who was once adamant about the importance of human decency.

Initially, I thought my own frustrations were merely the result of personal misfortune. But after taking a more objective look at the world around me, I’ve come to the disheartening conclusion that things are just as bad—if not worse—elsewhere. Take, for instance, a few recent academic job interviews. I was asked to conduct mock teaching sessions, and one of the most insightful, yet deeply depressing, pieces of feedback I received was that I needed to condense my material into easily digestible sound bites. The reason? "Students' attention spans nowadays are under a minute," I was told. Oh, marvellous. I’m sure the civil engineer designing a bridge can only focus for 45 seconds while framing the structure. Truly, this is a deeply reassuring thought.

But it doesn’t stop there. The media, a latecomer to the technology party, burst onto the scene with an enthusiasm only rivalled by a child with a new toy. Today, media outlets can hijack and shape the narrative in ways unimaginable to their predecessors. The swift transmission of information has turned the public into a fickle, easily manipulated mob. Everyone has become a believer or a fanatic, defending their chosen narrative with the fervour of a zealot, without so much as a glance at nuance or reason. The lines that once separated us are now drawn in the sand, with no room for debate or reconciliation. Whether it's the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, the Russo-Ukrainian War, the rise of Elon Musk and Dogecoin, or the endless spectacle of celebrity culture, the pattern remains the same. People don't seek truth; they crave simplicity — a black-and-white narrative that fits neatly within the confines of their biases.

The information we now have at our fingertips is limitless, and yet, the approach we take to it has become entirely hollow. Where once we prized thoughtful, scholarly debate as a means of enlightenment, it has now devolved into a performative spectacle. The ones with the most followers, the loudest voices, and the most eye-catching tweets win. The substance of an argument is no longer the deciding factor; it’s all about who can shout the loudest. The rise of influencers — those self-proclaimed "experts" in virtually everything — has relegated seasoned professionals and genuine specialists to the sidelines. Knowledge, once the domain of those who dedicated years to their craft, has been usurped by vapid personalities with massive social media followings. The credibility of an individual now rests not on their expertise, but on how many people they can convince to hit "like" or "subscribe."

The catalogue of our collective failures seems endless, and it leads me to wonder: are we really advancing, or are we simply regressing under the guise of progress? We like to think that with all our gadgets, apps, and instant access to information, we are somehow more enlightened than our forebears. But when you take a step back, it's hard to ignore the very real fact that, far from becoming wiser, we’ve nurtured a troubling ascent of the absurd.

The once fringe conspiracy theorists, the anti-vaxxers, and the flat-earthers, previously dismissed as harmless lunatics, are now afforded platforms to spread their irrationality to ever-larger audiences. The very people who a decade ago would have been the subject of ridicule are now influencing policy, shaping debates, and commanding the attention of millions. Meanwhile, the far right, with its views eerily reminiscent of those in 1930s Germany, isn’t just lurking in the shadows anymore; it’s out in the open, growing louder, and more disturbingly, it’s becoming normalised. A profoundly unsettling phenomenon, to be sure.

And yet, it doesn’t end with words or ideas. It has metastasised into something far more dangerous. Cyber warfare, once relegated to the pages of science fiction or the tedious courses designed to fill quotas in military academies, has now morphed into a legitimate and active force within the arsenals of most nations. No longer a distant possibility, we now witness cyber-attacks with disturbing frequency — drones deployed in targeted strikes, infrastructure crippling, data theft. And the latest reports, courtesy of The New York Times, inform us that artificial intelligence is now being employed for targeting and assessing military objectives with minimal human oversight. The supposed benefit? A reduction in collateral damage, as though minimising human cost, makes the entire enterprise somehow more palatable. This is the new face of warfare: cold, detached, and conducted with an efficiency that strips the humanity from the equation.

As we move forward, we may find ourselves trapped in a technological loop of our own making, one where the boundaries between morality and sanity are increasingly blurred. Technology has not just made us more capable; it has made us more dangerous.

It seems, with alarming clarity, that reality is now sprinting headlong into the arms of fiction. Technology, once hailed as the grand liberator and the savior of human progress, has, in the blink of an eye, transformed into a tool for unleashing our darkest and most pernicious instincts. Once upon a time, we were squeamish about the idea of technology enabling our vices. Now? Not so much. We’ve embraced it with a reckless abandon that would make even the most dystopian fiction blush.

Take OnlyFans—a platform that began with the noble intent of providing a space for creative artists to showcase their work. In a turn that would be laughable if it weren't so tragic, it's now mainstreamed as a digital marketplace for pornography. What began as a haven for personal expression has, with horrifying speed, been hijacked by the basest of impulses, reducing human interaction to an exchange of flesh and fantasy. And that, I’d argue, is a symptom of a larger malaise: the perversion of technology from a tool for good to one that exploits our most primal urges.

So, the question must be asked: Is Black Mirror right? Are we, in fact, living out a slow-motion villain arc, with technology as the willing accomplice? It’s a chilling thought, one that beckons us to consider whether we’re advancing or simply rushing toward the precipice, intoxicated by the shiny allure of our own creations. The very same tech that promised to liberate us is now handcuffing us to our worst impulses, making us mere spectators in a dark play of our own design.

☕ Love this content? Fuel our writing!

Buy us a coffee and join our caffeinated circle of supporters. Every bean counts!

Great column, but also terrifying. Many of these technological advances seem like they can also contribute to human flourishing, and yet as you correctly point out, they are exploiting our most basic urges. It is a shame, and I do not really see how to fight against these trends -- maybe trying to have an educated discourse with nuance...

And yet it seems it is not doing much. To what degree does substack play similarly as we all learn to use likes, comments, and subscriptions as a metric? Worse we may be under the illusion that we are making points, that we are engaging in dialogue when, in reality, we just found our silo where our ideas echo? I suspect, that if we make it through, there will be awe about just how unregulated all this was... much in the same way as we are sometimes in disbelief about the lack of regulations and safeguards in the past.

You wisely write, "And should any modern Cassandra dare suggest otherwise — that perhaps not every new gizmo is a gift from Olympus — they are swiftly branded a Luddite"

Human existence is rich in irony, and this is one of those.

The "more is better" relationship with knowledge which is the foundation of our science based civilization is a simplistic, outdated, and increasingly dangerous knowledge philosophy left over from the 19th century. But if you should suggest that maybe we should replace that outdated philosophy with an ability to manage the knowledge explosion (which inevitably will require saying no in some cases) you are labeled a Luddite by the science clergy.

The science clergy will insist that LEARNING SOMETHING NEW, how to actually take control of the knowledge explosion, is a backward Luddite idea. The science clergy wants to cling to the 19th century "more is better" knowledge philosophy, and that is labeled advanced.

The following article outlines the logic failure which keeps this sad irony alive....

https://www.tannytalk.com/p/the-logic-failure-at-the-heart-of